Access to Government Information

This section of the legal guide outlines the wide-array of information available to you from government sources. These sources range from your local city council all the way up to the largest agencies in the federal government. In fact, you might be quite surprised at how much information is available to you. And the best part is that you generally don't need to hire a lawyer or file any complicated forms -- you can access most of this information simply by showing up or filing a relatively simple request. Moreover, you don't need to be a professional journalist to share what you find with others who are interested in these issues; with nothing more than an Internet connection, you can make the information available to anyone in the world. For an impressive example of how some people are using the power of new information technologies in conjunction with government information, check out Adrian Holovaty's Chicagocrime.org, a browsable database of crimes reported in Chicago.

Regardless of what you publish online, it is likely that at least one (if not many) of the information sources we discuss in this section will be valuable to you. For example, you might want to find out whether the drinking water coming out of your faucet contains pollutants (information that is likely contained in documents held by the Environmental Protection Agency or one of its state counterparts). Perhaps you'd like to know more about how your local school board makes decisions (information that you can get by attending school board meetings). Or perhaps you are concerned that a real estate developer may have been sued for fraud (information that is available by visiting the courthouse in person or accessing the court's electronic docketing system).

Information from these government sources will be especially useful to you if you want to take your publishing activities beyond merely commenting on material posted by others. These sources can help you move into original reporting and enable you to comment in an informed fashion on local and national debates. You might even do a periodic post or column on subjects of particular interest to your website or blog. For example, the Gotham Gazette, an independent news site that covers "New York City News and Policy," has an entire section focusing on city government, which is largely based on meetings of the New York City Council.

We should point out, however, that the information you gather from these government sources doesn't have to be limited to the actions of the government itself. Government bodies collect extensive information on individuals, corporations, and other organizations. Much of this information is available to the public. You just have to know where to look.

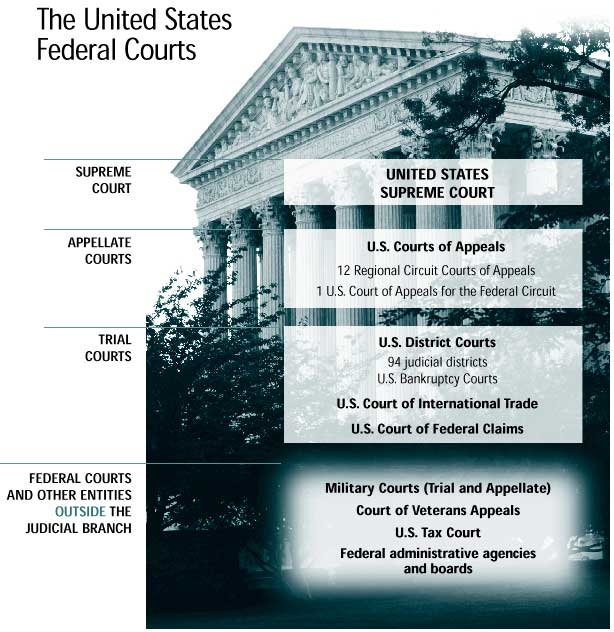

The first thing you will need to consider is which government entity likely has the information you are seeking. Public access to government information extends to a broad range of government sources, including federal and state agencies, Congress and state legislatures, government boards and committees, and the courts. In fact, it might be the case that the information you are interested in is located in more than one place. A little advanced research on your part can go a long way when dealing with the government. Because different laws apply to different government entities, you will want to review each section of this guide that might apply to your situation. If you are not sure whether the information you seek is associated with a federal, state, or local government body, refer to the page on Federal, State, and Local Government Bodies for some helpful information.

It is also worth bearing in mind that laws granting access to government information are only one of many important fact-finding tools in your information gathering toolbox. These laws can be very powerful, but their scope is limited to records and information available through government sources. For a broad overview of how you can investigate a full range of actors, including government, individuals, and corporations, see the Newsgathering section of this guide and check out the Center for Investigative Reporting's entertaining and inspirational guide, Raising Hell: A Citizens Guide to the Fine Art of Investigation.

Information Held by the Federal Government

The federal government is a sprawling and far reaching entity headquartered in Washington, D.C., but with agencies and offices in almost every part of the country. A number of important laws govern your access to information associated with the federal government.

The most well known of these laws is the Freedom of Information Act ("FOIA"), which provides access to the public records of most departments, agencies, and offices of the federal government. But several lesser known laws are also important, including the Government in the Sunshine Act which gives you the right to attend the meetings of many federal agencies, the Federal Advisory Committee Act, which allows you to attend the meetings of boards and committees that advise agencies of the federal government, and the Presidential Records Act, which sets out the procedures you must follow to request records from the president and his or her close advisers.

If you are seeking records held by a federal government agency, you should review the section on Access to Records from the Federal Government which describes FOIA and provides some practical advice on how to use the law to acquire government records. Keep in mind, however, that FOIA does not cover the President himself/herself, Congress, or the federal judiciary. For information on accessing information from these sources, see the Access to Presidential Records, Access to Congress, and Access to Courts and Court Records sections of this guide, respectively.

The federal government often acts through boards, committees, and other government "bodies." Examples include the Securities and Exchange Commission, the Federal Communications Commission, and the Federal Housing Finance Board. A common feature of these agencies, boards, commissions, and other government bodies is that they meet as groups to deliberate or take action on public business. If you wish to attend these meetings, you will need to become familiar with a category of laws called open meetings laws. These important laws give anyone, including members of the traditional and non-traditional press, the ability to attend the meetings of many federal government bodies and to receive reasonable notice of those meetings. In many instances, they also entitle you to obtain copies of minutes, transcripts, or recordings at low cost. See the section on Access to Government Meetings for more information and practical advice.

There are basically two types of federal government meetings you may wish to attend and each is governed by a different set of legal requirements. Federal agency meetings are governed by the Government in the Sunshine Act which gives you the right to attend the meetings of many federal agencies, such as the Federal Election Commission and the Federal Trade Commission. Federal advisory committee meetings, which are a strange hybrid type of meeting involving outside advisers tasked with giving advice to the federal government, are governed by the Federal Advisory Committee Act.

Information Held by State and Local Governments

Just as with the federal government, a number of important laws govern your ability to access information associated with state and local governments.

Every state has some version of a "Freedom of Information" (FOI) law — sometimes called a "sunshine law" — that governs the public’s right to access state government records. These FOI laws help the public keep track of its government’s actions, from the expenditures of school boards to the governor's decision to pardon prison inmates. For example, in 2003, a parent of a student in Texas, Dianna Pharr, spurred by the financial crisis in her local school district, began filing requests under the Texas Public Information Act to investigate the district's spending and operations. She and other parent volunteers established an online repository for the documents and made them available on a local community website, Keep Eanes Informed. Pharr's efforts received coverage in the local press, and have enabled her community to make informed decisions when dealing with school board proposals.

If the information you are seeking is contained in records held by your state or local government, you will need to review the section on Access to Records from State Governments in order to understand how to make a request under the relevant state law. For example, the California Public Records Act and the New York Freedom of Information Law govern access to records in California and New York, respectively. In many states, local government records can also be requested under the state open records law. Unfortunately, public officials sometimes deny that they are required to turn over information, deny that the public has any right to information, or fail to provide information in a timely way. To ensure that you get the information you need, you should review the section on Practical Tips for Getting Government Records.

If you are interested in attending the meetings of state or local government bodies, you should review the section on Access to State and Local Government Meetings. The most familiar examples of these kinds of government bodies at the local level include school boards, city councils, boards of county commissioners, zoning and planning commissions, police review boards, and boards of library trustees. At the state level, examples include state environmental commissions, labor boards, housing boards, and tax commissions, to name a few.

Courts and Court Information

The court system is yet another resource-rich place for you to access information. Your right to access the court system stems from the First Amendment, and has been expanded to give you the ability to attend almost all court proceedings and inspect public court records. The law provides important tools that you can use to help you understand the intricacies of a particular case, or watch how the court system performs. For example, you can use court records to check whether a doctor has previously been sued for malpractice, or to find the outcome of a criminal case.

You should first determine whether you need to access the information at the state or federal level. Once you’re armed with that knowledge, visit the pages that discuss access to court proceedings in federal court or state court, for information on your right to attend trials and other court proceedings. If, on the other hand, you want to review court records, such as legal complaints, motions, and other filings, visit the page on Federal Court Records or State Court Records, which describes your right to access court records and provides information on why your request may be denied, and how to appeal a denial. While there is no guarantee that you will get every court record or attend every court proceeding you desire, we've put together some tips that will help ensure that you take full advantage of the wealth of information available through state and federal courts. See the page discussing Practical Tips for Accessing Courts and Court Records for more information.

You may also wish to talk with the individuals associated with a court case. Visit the page on Access to Jury and Trial Participants to understand your ability to contact those who participated in the court proceeding such as the judge, lawyers, parties, witnesses, and jurors.

Getting Started

If, after reviewing the information in this section, you are still not sure where to start, you can always just browse one of the topics listed below:

- Access to Government Records: Describes federal and state freedom of information laws and provides practical advice on how to use these laws to acquire government records.

- Access to Government Meetings: Provides an overview of federal and state open meetings laws and explains how to assert your right to attend meetings held by federal, state, and local agencies, boards, committees, and other government bodies.

- Access to Congress and the President: Outlines the special set of rules that govern access to Congress and Presidential records.

- Access to Courts and Court Records: Provides an overview of federal and state laws that grant you the right to access federal and state court records and court proceedings.

Subject Area:

Access to Government Records

"Freedom of Information" ("FOI") is a general term for the laws — sometimes called "sunshine laws" — and principles that govern the public’s right to access government records. FOI helps the public keep track of its government’s actions, from the campaign expenditures of city commission candidates to federal agencies’ management of billions of dollars in tax revenues. Without FOI, information-seeking citizens would be left to the whims of individual government agencies, which often do not give up their records easily.

Using freedom of information laws is a simple, and potentially powerful, way of obtaining information about the activities of federal, state and many local governments. You don't need to hire a lawyer, and no complicated forms are involved—requests can be made in a simple letter. And you don't need to be a journalist to share what you find with others who are interested in these issues; with nothing more than an Internet connection, you can post the information and make it available to anyone in the world.

Your request can yield information that has a real impact on your community. For example, in 2003, a parent of a student in Texas, Dianna Pharr, spurred by the financial crisis in her local school district, began filing multiple requests under the Texas Public Information Act to investigate the district's spending and operations. She and other parent volunteers established an online repository for the documents she received and made them available on a local community website, Keep Eanes Informed. Pharr's efforts received coverage in the local press, and have enabled her community to make informed decisions when dealing with school board proposals. Similarly, in 2006, the nonprofit organization Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility used the Freedom of Information Act to get documents that revealed that genetically-modified crops had been sown on thousands of acres in a federal wildlife refuge. A coalition of nonprofits used this information to sue the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service for violating federal environmental law. For other examples of the benefits of sunshine laws, see the National Security Archive's 40 Noteworthy Headlines Made Possible by FOIA, 2004-2006.

So now that we've convinced you of the value of acquiring government records, it's time to dig into the relevant sections that govern the information you are interested in. Before you start, however, you'll want to first determine whether the information you seek is held by a federal or state governmental body. This is important because different freedom of information laws apply to the federal government and various state government entities. If you are not quite sure whether you should review the federal or state sections of this guide, you might find the page on Identifying Federal, State, and Local Government Bodies helpful.

The following pages in this section will help you to understand and use freedom of information laws to acquire government records:

- Access to Records from the Federal Government: If you are seeking records held by a federal government agency, you will need to review the section on Access to Records from the Federal Government which describes the federal Freedom of Information Act ("FOIA"). FOIA covers only national agencies, such as the Securities and Exchange Commission, the Environmental Protection Agency and the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. FOIA does not cover the President himself/herself, Congress, or the federal judiciary. For information on accessing information from these sources, see the Access to Presidential Records, Access to Congress, and Access to Courts and Court Records sections of this guide, respectively.

- Access to Records from State Governments: If you are seeking records held by your state or local government, you will need to review the section on Access to Records from State Governments in order to understand how to make a request under the relevant state legislation. For example, the California Public Records Act or the New York Freedom of Information law. In many states, local government records can also be requested under the state open records law.

- Practical Tips for Getting Government Records: Unfortunately, public officials sometimes deny that they are required to turn over information, deny that the public has any right to information, or fail to provide information in a timely way. To ensure that you get the information you need, you should review the section on Practical Tips for Getting Government Records.

Subject Area:

Access to Records from the Federal Government

If you are seeking records held by the United States government, you will need to become familiar with the Freedom of Information Act ("FOIA"), which was enacted in 1966. FOIA provides access to the public records of all departments, agencies, and offices of the Executive Branch of the federal government, including the Executive Office of the President. FOIA does not cover the sitting President, Congress, or the federal judiciary. For information on accessing information from these sources, see the Access to Presidential Records, Access to Congress, and Access to Courts and Court Records sections of this guide, respectively.

FOIA requires federal agencies to:

- Provide access to their records and information, barring certain exceptions;

- Suffer penalties for refusing to release covered information;

- Appoint a FOI officer charged with responding to information requests; and

- Publish agency regulations and policy statements, including their rules for handling FOIA information requests, in the Federal Register.

The heart of FOIA is a "FOIA request": a written notice to the FOIA officer of a federal agency stating which records you are seeking. You should be forewarned, however, that although FOIA is a powerful tool for getting government information, it involves a rather complicated set of procedures. Before you file a request, you should spend some time reviewing each of the sections listed below. Click on one of the following sections to get started:

- Who Can Request Records Under FOIA: Explains who is eligible to make a FOIA request.

- What Records Are Available Under FOIA: Describes what kinds of records can be requested, which agencies are covered, and what records are exempted.

- How to Request Records Under FOIA: Outlines the steps you should follow in making a request, and explains the procedures the government must follow in responding to a request.

- What Are Your Remedies Under FOIA: Describes the courses of action you can take to enforce your rights if you believe that your request has been wrongly denied.

Subject Area:

Who Can Request Records Under FOIA

The Freedom of Information Act ("FOIA") gives the right to request access to government records to any person for any reason, whether the person is a U.S. citizen or a foreign national. Requests can be made in the name of an individual or an organization (including a corporation, partnership, or public interest group). Individuals have the same access rights as professional journalists, though journalists who work for established media organizations sometimes receive better treatment from records-keepers. Individuals probably won’t qualify for some of the perks afforded to media professionals, such as fee waivers and expedited processing, but they are just as capable of using records requests to reveal information that is important to the public. In fact, according to one study, more FOIA requests come from ordinary citizens than from professional media organizations.

Filing a request under FOIA may seem daunting at first, and it often is not easy to figure out how and where to get the information you seek. However, this legal guide should help you navigate FOIA so you can gather valuable government information that you can use to inform your fellow citizens and the world at large.

Subject Area:

What Records Are Available Under FOIA

FOIA covers records from all federal regulatory agencies, cabinet and military departments, offices, commissions, government-controlled corporations, the Executive Office of the President, and other organizations of the Executive Branch of the federal government. 5 U.S.C. § 552(f). For example, the Environmental Protection Agency, the Defense Intelligence Agency and the Food and Drug Administration are all covered by FOIA. To browse a list of executive agencies, visit the U.S. Government Manual or the LSU Libraries Federal Agency Directory. Links to a number of federal agencies' FOIA websites are available here.

FOIA does NOT apply to the President, Congress (or members of Congress), or the federal courts and federal judiciary. For information on accessing information from these sources, see the Access to Presidential Records, Access to Congress, and Access to Courts and Court Records sections of this guide, respectively. Some federally funded organizations may not be covered by FOIA if the government does not control or regulate their operation. However, any of those organizations’ records that are filed with federal agencies may be covered. No private persons or organizations are covered by FOIA.

State and local governments are not covered by FOIA, including federally-funded state agencies, but all states and some local governments have passed freedom of information laws. Requests for information from a state or local governments must be made under that jurisdiction's freedom of information legislation. For more information on selected states, see the Access to Records from State Governments section of this guide.

All non-exempt electronic and physical records held by federal agencies must be disclosed under FOIA. Federal agencies covered by FOIA are permitted to withhold documents, or redact portions of documents, if the records (or information in the records) are covered by one of the nine exemptions established by FOIA. One of the most common exemptions relied on the exemption for national security.

The following section set out the essential information you need to know about the kinds of documents you can access using FOIA, so that you can tailor your request or, if your request is denied, to consider whether and how to this decision might be challenged.

- Finding and Getting the Records You Seek: Your first task should be to determine where the records you are interested in are located and if the information you want is already publicly available.

- Types of Records Available under FOIA: While the types of records available under FOIA is quite broad, FOIA may not apply to everything you want. Review this section to determine what types of records you can request.

- FOIA Exemptions: Before making a request, you should determine whether the records you are interested are be covered one of FOIA's exemptions, which could result in the agency denying all, or part, of your request.

Subject Area:

Finding and Getting the Records You Seek

There are a number of ways that you can receive government records. The easiest method is to access an agency's online “reading room” which provides free access to certain government documents. If you can't get what you want through a reading room, you should carefully consider how (and in what form) you want the responding agency to provide the documents to you.

Before you jump into filing a FOIA request, however, you should spend some time researching which agency or agencies have the records you want. There is no central depository for federal government information, and each agency has its own office for handling FOIA requests. This can make your search rather difficult, but there are a number of resources that may help you in determining which federal entities are likely to have the information you seek:

- The United States Government Manual contains a list of federal agencies and a brief description of their functions. The Manual also contains the addresses and telephone numbers for each agency.

- Online Directories to Government Information provide information on which agencies have responsibility for various subject areas.

- The Library of Congress provides links to congressional committees, publications, and other information. While Congress is not subject to FOIA, the Library of Congress has extensive records on many government agencies.

- The National Archives and Records Administration contains extensive records from across the federal government, including the historical records of federal agencies, congressional bodies, and courts.

Online Reading Rooms

FOIA requires that all federal agencies maintain online reading rooms that provide electronic versions of their regulations, policy statements, and records. Reading rooms are the easiest method of obtaining certain types of government information, because accessing them requires only a few clicks on an agency’s website. Therefore, you should always start by checking to see if the records you are seeking are already available in the reading room. This will save you the time, energy and money of making a FOIA request or otherwise attempting to get information. The type and amount of information available in the reading rooms vary greatly by agency, but many include a number of useful records.

If you can't find the agency's online reading room from their homepage, try searching for “(agency name) reading room” (most agency web sites have a section labeled specifically as a “reading room,” so you should be able to find it with a simple online search). It can also be helpful to run the same search at FirstGovSearch.gov, the U.S. Government Printing Office’s online directory of government information.

Here is a list of online reading rooms for some of the government’s most visible agencies and offices:

- The Department of Justice

- Central Intelligence Agency

- Internal Revenue Service

- Federal Bureau of Investigation

- U.S. Department of State

- Office of the Attorney General

Other Means of Getting Records

If you can't find the records you are seeking in the agency's reading room, then you will need to request the records informally or file a FOIA request. See the section on Requesting Records Under FOIA in this guide for more information.

In your request you can ask to receive either an electronic copy or a physical copy of the records. If the records already exist in the form that you request them in, then the agency must generally provide the records in your preferred form. However, if you request an electronic copy of records that only exist in paper form, then the agency must only provide you with an electronic copy if it is reasonably able to do so, meaning that the record is "readily reproducible" in the alternate format. If you would prefer a certain type of electronic format, the agency need only provide the records in that specific format if it is reasonably able to do so. See 5 U.S.C. 552(a)(3)(B).

Depending on the agency, physical copies of records may usually be mailed or faxed to you, while electronic copies of records may either be e-mailed to you or sent to you on a CD-ROM or other disk drive. Because of the various ways you can receive the records, it is very important that you specify your preferred method when you initially file your request.

Subject Area:

Types of Records Available under FOIA

Any records created, possessed, or controlled by a federal regulatory agency, cabinet and military departments, offices, commissions, government-controlled corporations, the Executive Office of the President, and other organizations of the Executive Branch of the federal government must be disclosed unless the information contained in the records is covered by a specific FOIA exemption. FOIA only extends to existing records; you cannot compel an agency to create or search for information that is not already in its records. Nor can you use FOIA to compel agencies to answer your general questions under FOIA. However, you sometimes can agree to accept information in an abbreviated form rather than the actual documents.

Agencies are required to make the following records available for public inspection and copying without a formal FOIA request via the Federal Register:

- final opinions made in the adjudication of cases;

- unpublished policy statements and agency interpretations;

- staff manuals that affect the public;

- copies of records released in response to previous FOIA requests have been or will likely be the subject of additional requests; and

- a general index of released records determined to have been or likely to be the subject of additional requests.

If you are interested in records that don't fall into one of these categories, you will need to file a FOIA request. See the section on How to Request Records Under FOIA in this guide for more information.

Physical Records

Physical records of any description can be requested under FOIA. Traditional typed documents, as well as maps, diagrams, charts, index cards, printouts and other kinds of paper records can be requested. Moreover, access under FOIA is not restricted to information recorded on paper. Information recorded in electronic media (see further below), audio tapes, film, and any other medium can be requested. The Society of Professional Journalists' A-Z list of covered documents is a great place to start if you aren’t sure if the record you want is covered by FOIA.

Electronic Records

The increasing availability of electronic versions of government records is one of the most important developments in public access to government information. “E-records,” as these records are sometimes called, generally are simpler and quicker to obtain, easier to analyze, and otherwise better suited to citizen use. With the invention of online reading rooms and FOIA sections of agency websites, many records take no more effort to access than personal e-mail. Information from e-records can be organized into databases, searched, and plugged into tables and charts, making it possible to perform in-depth analysis in much less time—which opens up new possibilities for public use of government information.

Besides quicker access and (possibly) cheaper reproduction costs, electronic records have several advantages over their paper-based counterparts. E-records can be compiled into databases for easy searching and comparison. They are easier to sort through quickly, possibly making it easier to find patterns and discrepancies. This can make the information-gathering process significantly simpler and more efficient, which is a great help to those who don’t have the time and resources to mount in-depth investigations. For more information on ways to use electronic records, the Poynter Institute has an online bibliography of computer-assisted reporting (CAR) primers and other sources of information.

Electronic records are becoming more and more prevalent as the government continues to expand its use of technology. Because of this, any record you seek could be available in electronic format. Whether you’re talking directly to a records-keeper or filing an official FOIA request, you should consider asking for electronic copies of the records you are requesting. Depending on the agency, you may be able to specify whether you receive e-records by e-mail attachment, CD, or other medium. Some states, for instance, allow the requester to receive records in the format of their choice. An agency must make requested records available in electronic format at the request of a person if the record is readily reproducible by the agency in electronic format (§ 552(a)(3)(B)).

Congress extended the Freedom of Information Act to electronic records by enacting the Government Printing Office Electronic Information Enhancement Act of 1993 ("Electronic Information Act") and the Electronic Freedom of Information Act Amendments of 1996 ("E-FOIA"). The Electronic Information Act requires government to maintain an online directory of Federal electronic information, including the Congressional Record, the official record of Congress’ proceedings and debates, as well as the Federal Register, which contains agencies’ regulations and policy statements. E-FOIA requires that government agencies:

- prepare electronic forms of records and record indexes;

- offer access to those records;

- have a FOIA section of their websites, on which they must post agency regulations, administrative opinions, policy statements, staff manuals, and other records;

- identify common records requests and make those records available online;

- create online reading rooms that include information available in traditional reading rooms; and

- create reference guides for accessing agency information, which must be available online.

Subject Area:

FOIA Exemptions

While the records you've requested might be covered by FOIA, the information contained in the records may relate to certain subject areas that are exempt from disclosure under FOIA. FOIA contains nine exemptions that might impact your request:

- Classified Documents--information classified in the interests of national security or foreign policy can be withheld (§ 552(b)(1)(A)).

- Internal Agency Personnel Rules-- information relating to internal agency practices is exempt if it is a trivial administrative matter of no genuine public interest (e.g., a rule governing lunch hours for agency employees) or if disclosure would risk circumvention of law or agency regulations (e.g., an employee's computer user id) (§ 552(b)(2)).

- Information Exempt Under Other Laws--an agency is prohibited from disclosing information that protected from disclosing under other federal laws. For example, federal tax laws prohibit the disclosure of personal income tax returns (§ 552(b)(3)).

- Trade Secrets or Confidential Commercial Information--this exemption applies to trade secrets (commercially valuable plans, formulas, processes, or devices) and commercial information obtained from a person (other than an agency) that would be likely to harm the competitive position of the person if disclosed (such as a company's marketing plans, profits, or costs (§ 552(b)(4)).

- Internal Agency Memoranda and Policy Discussions--in order to protect the deliberative policymaking processes of government, internal agency memoranda and letters between agencies discussing potential policy options are exempted from disclosure (§ 552(b)(5)).

- Personal Privacy--private data held by agencies about individuals is exempt if disclosure would constitute a clearly unwarranted invasion of privacy, but a person is not prevented from obtaining private information about themselves (§ 552(b)(6)).

- Law Enforcement Investigations--this exemption allows the withholding of information that would, among other things, interfere with enforcement proceedings or investigations, deprive a person of a right to a fair trial, breach a person's privacy interest in information maintained in law enforcement files, reveal law enforcement techniques and procedures, or endanger the life or physical safety of any individual (§ 552(b)(7)).

- Federally Regulated Banks--information that is contained in or related to reports prepared by or for a bank supervisory agency such as the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, the Federal Reserve, are exempt (§ 552(b)(8)).

- Oil and Gas Wells--geological and geophysical data about oil and gas wells are exempted from disclosure (§ 552(b)(9)).

It is beyond the scope of this guide to describe each exemption in exhaustive detail. Suffice it to say, most FOIA disputes involve disagreements over the scope and application of these exemptions. For more information on each exemption, see the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press's excellent booklet on How to Use the Federal FOI Act.

Other than exemption number 3 -- which relates to information exempt under other federal law -- these exemptions are permissive, not mandatory. This means that FOIA allows an agency to refuse to disclose otherwise covered records, or to redact portions of documents, but it does not compel the agency to do so. For more on the discretionary nature of these exemptions, see the U.S. Department of Justice's FOIA Guide.

An agency must state which exemption it is relying on when it withholds documents or redacts information. In addition, agencies are required to disclosure all non-exempt information, even if it is contained in a record that contains other information that is exempt from disclosure. In other words, if an exemption only applies to a portion of a record, the agency must release the remainder of the document after the exempt material has been redacted.

If you believe an agency has improperly used one of these exemptions to deny your request, see the section of this guide on What Are Your Remedies Under FOIA which describes the courses of action you can take to enforce your rights under FOIA.

Subject Area:

How to Request Records Under FOIA

Before making a FOIA request, you should first try to obtain information by quicker, less formal means. You can access many records without going throught the formal FOIA request process. The easiest way to access some records is via the Internet, through the Federal Register or agencies’ online reading rooms.

FOIA requires agencies to publish the following information in the Federal Register:

- Descriptions of the agency's organizational structure and the addresses of offices where the public may obtain information

- General descriptions of the agency's operation

- FOIA procedures and descriptions of forms

- Substantive rules of general applicability and general policy statements

Reading rooms are typically accessible from the agency’s website. For more information on reading rooms, refer to the legal guide’s section on Finding and Getting the Records You Seek. Agencies also maintain physical reading rooms, which could be useful if you are able to visit their offices.

If the information is not available online, you can try simply asking for it. Agencies are required to make the following records available for public inspection and copying without a formal FOIA request:

- final opinions made in the adjudication of cases

- unpublished policy statements and agency interpretations

- staff manuals that affect the public

- copies of records released in response to previous FOIA requests that are of sufficient interest to the public that they will likely be the subject of additional requests

- a general index of released records determined to have been or likely be the subject of additional requests

Explain what records you’re seeking and that you’re prepared to file an official request if necessary. A record-keeper familiar with FOIA might honor a request made in-person or via telephone, saving both you and the agency time and (possibly) money. If that doesn’t work, you can try speaking to the agency’s FOIA officer.

If you cannot access the records through these informal means, you then will need to file a formal FOIA request. Click on one of the links below to get started:

Subject Area:

Filing a FOIA Request

Written requests are the only way to legally assert your FOIA rights. These should be mailed, faxed, e-mailed, or hand-delivered to the relevant agency’s offices, depending on which methods the agency allows. A quick online search of the "agency's name" and "FOIA" should provide you with specific information about how the particular agency accepts FOIA requests. If you can't find the information through an online search, check the Federal Register, which should include this information.

A FOIA request should be addressed to the agency's FOIA officer or the head of the agency. It must include:

- Your name and contact information, including your address if you want the records mailed to you or your e-mail address if you are requesting that electronic records be e-mailed to you.

- A statement that you are seeking records under the Freedom of Information Act.

- A description of the record(s) you are seeking. The only requirement is that you “reasonably describe” the records. Basically, this means that you must give enough information that a record-keeper would be able to find the records without an undue amount of searching. It is generally advisable to make the request as specific as possible, so if you know the title or the date of a particular document, or can precisely describe the class of documents you seek, you should set out these details. Being specific helps you avoid paying fees for records that you actually do not need and helps to expedite your request. See the section on What Records Are Covered in this guide for more information on the types of records you can request.

In addition to the required elements listed above, you might want to include some of the following additional information in your request:

- Your preferred method of contact for any questions about the record(s) you are seeking, whether it be mail, e-mail, or telephone.

- Your preferred medium for receiving the record(s), such as paper, CD-Rom, microfiche, e-mail attachment, etc. (note that you are not always guaranteed to receive the records in your preferred format, but the agency will attempt to honor such requests if possible). See the section on Requesting Electronic Records in this guide for more information.

- You do not need to tell the government organization why you want the information; every person has a right to request records regardless of his or her profession. That said, you may want to inform the record-keeper that you plan to use the information to publish on a matter of public interest.

- A request for a fee waiver or expedited review for your request, if applicable, as discussed in the Costs and Fees and Time Periods under FOIA sections of this guide.

- The maximum fee you are willing to pay for your record(s). You should indicate that you wish to be contacted if the charges will exceed this amount.

The Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press and the The U.S. Department of State both offer forms that will automatically generate a FOIA request for you. These can be an excellent way to get started.

Where to Send Your Request

Your FOIA request should be addressed to the relevant agency's FOIA officer or the head of the agency. The U.S. Department of Justice has a fairly comprehensive list of FOIA contacts at federal agencies. If the agency you want isn't listed there, you can usually find the information easily by conducting a quick web search; just type in "agency's name" and "FOIA contact."

If you are unsure of which agency to send your request to, the US Government Manual may be of assistance. You will likely receive a faster response if you make your request in accordance with the agency's own FOIA regulations (these can be viewed in the Code of Federal Regulations), but the above minimum requirements are sufficient to make a valid FOIA request.

Subject Area:

Time Periods under FOIA

Technically, government organizations must respond to a FOIA request with a denial or grant of access within 20 business days. Note that the agency must only respond within 20 days; it does not have to deliver the records within the 20-day time period. The time period does not begin until the proper agency or office actually receives your request. Furthermore, under the new 2007 FOIA amendments, the agency may exceed the 20-day time limit if it needs to request more information from you in order to process your request.

Agencies may extend this time limit by up to 10 additional working days (they must informing you they are doing so) if one of the following "exceptional circumstances" exists: the record-keeper must search an extraordinary amount of records; the search involves records from multiple offices; or the search involves records from multiple organizations. See the FOIA Guide's section on time limits for a more detailed explanation. If your request cannot be fulfilled within these time periods, the agency may ask you to reasonably modify your request or allow for an alternative time frame.

Realistically, many agencies do not comply with these time limits. Some agencies may have a large backlog of requests, and they are usually permitted to treat requests on a "first come, first served" basis as long as they devote a reasonable amount of staff to responding to the requests. These agencies generally have a processing system that allows simpler requests to be handled quickly so that these requests do not have to "wait in line" behind more complex requests.

However, as of December 1, 2008, FOIA will be amended to require that agencies waive all search and duplication fees if they fail to comply with time limits and none of the "exceptional circumstances" listed above exist. It is yet to be seen if this will speed up agencies' response times.

Expedited processing

FOIA provides for requests to receive “expedited review” if the request meets certain requirements. Generally speaking, you will be entitled to expedited treatment if health and safety are at issue or if there is an urgent public interest in the government activity at issue.

If you think there is a compelling reason why you need the information sooner than the normal period under FOIA, you should clearly explain your reasons in your initial FOIA request. Agencies must decide whether or not to grant expedited processing within 10 calendar days of the request. Aside from these specific circumstances listed above, agencies may use their discretion in deciding whether or not to grant expedited review. So, it doesn’t hurt to ask even if you don’t meet the requirements.

You should also check the individual agency's requirements to see if they allow other types of requests to receive expedited treatment. The Department of Justice, for instance, offers expedited review “for requests concerning issues of government integrity that have already become the object of widespread national media interest” or “if delay might cause the loss of substantial due process rights,” (see the DOJ reference guide section on expedited processing).

Checking the Status of Your Request

Under the 2007 FOIA amendments, the agency must provide you with a tracking number if your request will take longer than 10 days to process. Then, if you haven't heard back from an agency or are unsure about the status of your request, you can use the tracking number to find out more information. Each agency is required to have at least one "FOIA Requester Service Center" that can give information about the status of pending FOIA requests. The agency must tell you the date that it received your request and must give an estimated date that it will complete your request. The centers can generally be contacted by mail, e-mail, or telephone.

If the deadlines have passed and you haven't been able to get any information from the agency about the status of your request, you should review this guide's section entitled What Are Your Remedies Under FOIA to see what your options are.

Subject Area:

Costs and Fees

Federal agencies are allowed to charge “reasonable” costs for responding to your FOIA request. This typically includes fees for the time the record-keeper spends searching for the correct documents as well as the cost of duplicating those documents. See 5 U.S.C. 552(a)(4)(A).

FOIA breaks down requesters into three categories for determining fees:

- Commercial use requesters, who must pay all fees for search, duplication, and review

- Requesters from the professional media, educational institutions, and scientific institutions, who do not have to pay search fees and only pay duplication costs after the first 100 pages

- All other requestors, who pay search fees after the first two hours and duplication costs after the first 100 pages

Note that this means that small requests should always be free as long as the information is not intended for commercial purposes. Also, you should always be as specific as possible when describing the documents in your initial FOIA request. This will reduce the amount of time that the record-keeper must spend searching for the documents, which will potentially save you money.

Non-traditional journalists generally will fall into the last category -- and thus may be on the hook for search fees -- even if they intend to publish the information in blogs, websites, or other media. If you are not associated with professional media, you can always request that you should be considered under the second category because of your intent to publish. The New FOIA Reform Act, which goes into effect in December 2008, seems to broaden the scope of the "professional media" category. Under the new amendment, a person can be considered part of the news media if he or she gathers information that is of public interest, creates a distinct work, and distributes that work to an audience. However, the Reform Act cautions that this is not an all-inclusive category, so it remains to be seen if bloggers and other citizen journalists will be able to benefit from fee waivers generally only reserved for "professional" media. We've been following this issue in our blog, and you can read more about the new definition here.

The Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press's FOIA Guide breaks down some of the actual fees you can expect to pay:

Search fees generally range from $11 to $28 per hour, based on the salary and benefits of the employee doing the search. Fees for computer time, which are described in each agency’s FOI regulations, vary greatly. They may be as high as $270 per hour. Photocopying costs are normally between 3 and 25 cents per page.

If you think your request could involve a significant amount of search time or copying, make sure your FOIA request includes a limit on the fees you’re willing to pay. You may also want to ask in advance for an estimate of what the expected fees may be.

Here are some additional things to keep in mind when dealing with fee issues:

- Agencies can charge search fees even if they don’t find any documents that satisfy your request, since the futile search still took time.

- As long as you aren’t requesting the information for commercial purposes, agencies cannot charge you for time they spend deciding whether documents should be exempt or time they spend blacking out restricted information from the documents.

- Organizations can’t require you to pay in advance if the expected fee is less than $250 and you don’t have a prior history of failing to make payments with the organization.

- Under FOIA, organizations are required to publish fee schedules in the Federal Register. An organization’s FOI officer should be able to provide you with the schedule, though some are available on organizations’ websites. The fee schedule includes information about how much the particular agency charges for searching, copying, etc.

- You can always try asking the organization to waive or reduce fees, even if you haven't formally requested a fee waiver.

Fee waivers and fee reductions

Under the Freedom of Information Reform Act of 1986, your FOIA requests could be eligible for total or partial waiver of fees if you can show that the disclosure of the information is in the public interest—even if you aren’t a professional journalist. This requires that you specifically request a waiver or reduction of fees and explain why you think the public has an interest in understanding the information. See the DOJ's FOIA Guide for more information about the "public interest" fee waiver. You also must explain any financial interest you have in the information, though a financial stake in publishing the information -- such as if you are paid to blog -- should not pose a problem.

Agencies consider fee waiver requests on a case-by-case basis. You can appeal fee or waiver decisions in the same way you appeal request denials. See the section on What Are Your Remedies Under FOIA in this guide for more information.

Subject Area:

What Are Your Remedies Under FOIA

You have several options if your FOIA request is denied in whole or in part. First, you can attempt to resolve informally any disputes you have with the responding agency. If informal resolution fails, you should appeal the denial within the relevant agency before taking any other action. If your appeal is unsuccessful and the agency withheld the information because it is classified, you can apply to have the information declassified. If these options have failed to resolve the dispute, you can seek mediation through the newly authorized FOIA ombudsman or file a lawsuit in court to enforce your rights under FOIA.

Each of these options is described briefly in this section.

Informal Resolution

The simplest -- and often most effective -- remedy is to seek informal resolution of the dispute. Delays are frequently due to the overworked nature of most FOIA officers. Your offer to "revise" or "narrow" the scope of your request can go a long way toward getting faster, and better, treatment of your request. If you revise your request, be sure to make clear that you willingness to compromise is not considered a "new" request by the agency (a new request will start the FOIA clock running again). If the agency tells you that the records don't exist, ask them to describe their search methodology. Perhaps they aren't looking for the right things or in the right places. It might also help if you offer to resolve fee or fee waiver issues by paying a small amount.

While you engage in informal resolution be sure and keep records of all of your contacts with the agency. Track all time and response deadlines carefully.

Appealing within the Relevant Agency

If the agency denies your request or does not respond within the required time period, you can appeal to the agency's FOIA Appeals Officer. If the agency sent you a denial letter, it should set out the agency's appeal procedures. Take special note of the time limitation for appeals, which are usually around thirty days. If you haven't received any response from the agency (an excessive delay in complying with a request constitutes a denial under FOIA) you should send your appeal to the head of the agency.

Appeal letters can be used to challenge the agency's failure to respond in a timely fashion, a decision not to release records in whole or in part, the adequacy of the search used to locate responsive records, and the agency's refusal to grant you a fee waiver.

In your FOIA appeal letter you should:

- Cite section 552(a)(6) of FOIA and clearly list your grounds for appeal;

- Attach copies of the original request letter and the denial letter;

- Take some time to explain the reasons why the denial should be reconsidered (for example, because the exemption does not properly apply to the document, or because the agency should waive the exemption in the current case); and

- State that you expect a final ruling on your appeal within 20 working days, as required by FOIA.

Sample appeal letters can be found on the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press' website and at the National Security Archive.

Make sure you are familiar with the exemptions to FOIA so you can argue that the records you are seeking are not or should not be exempted. See the section on FOIA Exemptions in this guide for more information.

If the agency denies your appeal or does not respond within 20 days, you may file a lawsuit in federal court (see below).

Declassification

If the agency denied your request because the information is classified (i.e. the agency relied on the national security exemption), you can make a separate request for mandatory declassification review of the information. You can learn more about declassification review procedure by going to the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press' FOIA Guide.

Mediation

Currently there is no mediation available for FOIA disputes. However, the Open Government Act of 2007, which amends FOIA, provides for the establishment of a new FOIA ombudsman, the Office of Government Information Services, to mediate such disputes. There is some uncertainty about whether the Office will be an organ of the more independent National Archives and Records Administration or the Department of Justice (which defends lawsuits against agencies that refuse to furnish requested documents) (see this Washington Post article and Senator Leahy's Senate address on the issue).

Once the situation is clarified, we will update this section with the procedures for instituting FOIA mediation.

Filing a Lawsuit

If your request is denied, and your internal appeal does not reverse this decision, you may sue the agency in the United State District Court in your state of residence, in the state where the records are located, or in the District of Columbia. It is generally recommended that you retain an attorney to bring such a suit. If your lawsuit is "substantially successful", the agency will be ordered to pay your attorney's fees. See the section in this guide on Finding Legal Help for help with hiring lawyer or getting other assistance.

However, you have the right to appear on your own behalf in court by filing a complaint pro se. If you decide to do this, you will find the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press' sample complaint for a FOI records denial and Public Citizen Litigation Group's Sample FOIA Litigation Documents very useful.

Obtaining records through legal action can be a costly and drawn-out process. Some lawsuits over FOIA denials can last more than a year. If you assert that there is a public interest in your timely access to the records, the court could speed up your case through “expeditious consideration.”

Lastly, keep in mind that if you file a lawsuit, you must do so within six years from the date of your initial FOIA request, even if you receive no response or an incomplete response from the agency.

Subject Area:

Access to Records from State Governments

You can access a vast number of state government records by using your state's freedom of information law. All fifty states and the District of Columbia have freedom of information laws granting public access to state government records, most of which are based at least in part on the federal FOIA. However, the laws can vary widely from who can make the requests, to which government body is required to provide access to its records, to the formalities a request must meet.

Choose your state from the list below for state-specific information on accessing each state's public records. (Note: This guide currently covers only the 15 most populous states and the District of Columbia. We hope to add additional states to the guide at a later date.)

Subject Area:

Access to Public Records in Arizona

Note: This page covers information specific to Arizona. For general information concerning access to government records see the Access to Government Records section of this guide.

Anyone can inspect or copy all records maintained by any Arizona public body during office hours, pursuant to Arizona law, §§ 39-101-39.161. Generally you don't have to give an explanation, unless the records are to be used for commercial purposes. If so, you will have to state that use and the Governor can, by executive order, prohibit their release.

If the records are released for a commercial purpose, then you may also be charged a portion of the cost for getting the copies, a fee for time, materials and personnel, and commercial market value of the reproduction, pursuant to 39-121.03.

If you have a commerical purpose and don't say so, you may have to pay damages up to three times the amount that would normally be charged, plus costs and attorney fees. So, if you have a commerical purpose for the records, make sure you say it when requesting the records!

What Records Are Covered in Arizona

What Government Bodies Are Covered

You should be able to request records from any any subdivision of the state, county, municipality, school district, or any committee or subdivision supported by or spending state money. Any person elected or appointed to any public body is subject to the open records law. Any records they maintain on their offical activities or any activities supported either by state money or a state political subdivision are considered public, under § 39-121.01.

What Types of Records Can Be Requested?

If records aren't available online and you aren't able to go to the office, you can request the records to be mailed to you. However, the record custodian may request advance payment for copying and postage, so be ready to pay up front.

As of 2010, you can now request budgets of charter schools, actions of the State Board of Dental Examiners, and records of any abortions and/or abortion complications performed at any medical facility in the state. You can also access any contract that involves state funds online.

Any expense reports by political parties concerning campaign expenses are now public.

Exemptions

Any agency that denies your request must furnish an index of records that have been withheld and the reason for each — but only if you ask for it. The department of public safety, the department of transportation motor vehicle division, the department of juvenile corrections and the state department of corrections are exempt from this requirement.

Certain records relating to "eligible persons" (peace officers, justices, judges, public defenders, prosecutors, probation officers, law enforcement, national guardsmen, and anyone protected by court order) are exempt from disclosure pursuant to § 39-123. You have no right of access to any of the following records, if it relates to an eligible person:

- The home address or home telephone number, unless the office gives written consent or the record's custodian finds that a release would not create a reasonable risk of injury or damage to property.

- A photograph of any eligible person, unless the officer has been arrested or formally charged with a misdemeanor or felony, or if you work for a newspaper and you are requesting the record for a "specific newsworthy event." This won't apply if the officer is working undercover or if disclosure is not in the state's best interest. (This prohibition doesn't apply if: the picture is being used to make a complaint against the officer; if obtained from a source other than the law enforcement agency; or, the officer is no longer employed by the state.)

Any law enforcement agent who improperly discloses this information is guilty of a felony, so be wary if any officer gives you this information.

The law also exempts all archaeological discoveries and risk assessments of any energy, water or telecommunications infrastructures.

As of 2010, you no longer can access the names of any indivduals/firms who are applying for government contracts until the contract is complete. Also, all working papers and audits are exempted.

The Arizona Court of Appeals has indicated that trade secrets contained in public records may be protected by the confidentiality exemption to Arizona's public records laws. Phoenix Newspapers, Inc. v. Keegan, 35 P.3d 105, 112 (Ariz. Ct. App. 2001).

How to Request Records in Arizona

Making the request

The law doesn't require any specific way of requesting records, so long as you request them during normal office hours. If the custodian doesn't respond to you promptly or give you an index when you ask for one, the law deems your request "denied" and you may pursue other remedies.Payment

The custodian of the records may charge you for access, but the law doesn't specify any amount. The exception is records listed in §§ 39-122 through 39-127, related to records used in claims against the United States. If you are requesting records for that purpose, the custodian can't charge you.What Are Your Remedies in Arizona

If you've been denied access to open records you may sue the official who denied you, and you also may appeal to the superior court. If you win, the court may give you an amount to pay your attorney any fees you incurred in the suit, along with other legal costs (such as filing with the court, etc.) However, make sure you sue within one year of being denied access, pursuant to Arizona code § 12-821.

Jurisdiction:

Subject Area:

Access to Public Records in California

Note: This page covers information specific to California. For general information concerning access to government records see the Access to Government Records section of this guide.

You have a statutory right to inspect a vast number of California's public records using the state's California Public Records Act (CPRA). See the text of the CPRA in sections 6250 and 6253 of the California Government Code (Cal. Gov't Code), which states that any individual, corporation, partnership, limited liability company, firm or association, both in and out of California, can inspect California public records.

You are not required to explain why you are making a request. However, if you request the disclosure of the address of any individual who has been arrested, or the current address of the victim of a crime, you must state whether the request is made for a journalistic, scholarly, political or governmental purpose, and declare that the information will not be used to sell a product or service. Cal. Gov't Code § 6254(f)(3).

What Records Are Covered in California

What Government Bodies Are Covered

You can inspect the public records of California state offices, officers, departments, divisions, bureaus, boards and commissions, and other state bodies and agencies. You can also inspect the public records of local agencies, including counties, cities, schools districts, municipal corporations, districts, political subdivisions, local public agencies, and nonprofit entities that are legislative bodies of a local agency. However, you will not be able to access the records from the California state legislature or its committees, nor to the state courts under the CPRA. See Access to Government Meetings and Access to Court Records for more information.

What Types of Records Can Be Requested

You can inspect all "public records" of the government bodies subject to the CPRA. The term "public records" is broadly defined to include information relating to the conduct of the public's business that is prepared, owned, used, or retained by any state or local agency regardless of what medium it is stored in. See Cal. Gov't Code § 6252(e).

Note that public records do not extend to personal information

of public officers which are unrelated to the conduct of public

business (for example, a phone message taken by a public officer from a

colleague's wife about picking up the children), or computer software

developed by the government.

Exemptions

An agency may refuse to provide a record if, in a particular case, "the public interest served by not making the record public clearly outweighs the public interest served by disclosure of the record." [Cal. Gov't Code § 6255]. For more information, visit California First Amendment Coalition's FAQs on the general public interest exemption.

In addition to this general exemption, an agency is entitled (but not required) to refuse disclosure if one or more of the following narrowly construed statutory exemptions applies. The Act sets out a long list of specific exemptions (Cal. Gov't Code § 6254), including:

- Preliminary drafts, notes or memoranda. Pre-decisional, deliberative communications which are not retained by the public agency in the ordinary course of business need not be disclosed if the public interest in withholding those records clearly outweighs the public interest in disclosure (see California First Amendment Coalition's FAQs on this exemption).

- Pending litigation. This exemption applies to documents pertaining to pending litigation to which the public agency is a party, including attorney work product and documents produced by the agency in anticipation of litigation, but not including deposition transcripts (see California First Amendment Coalition's FAQs on this exemption).

- Private personal information. Files pertaining to the personnel, medical, wage, financial, job applications or similar matters are exempted from disclosure if disclosure would constitute an unwarranted invasion of personal privacy (see California First Amendment Coalition's FAQs on this exemption).

- Securities and banking regulators. Applications and other confidential information received by, and reports and draft commmunications produced by/for, these state agencies are exempt from disclosure.

- Geological and geophysical data. This exemption applies to plant production data and similar information relating to utility systems development, or market or crop reports, which are obtained in confidence.

- Law enforcement. Records of complaints, investigations, intelligence records, security procedures and other documents of law enforcement agencies are exempted from disclosure (see California First Amendment Coalition's FAQs on this exemption).

- Examination data. Test questions, scoring keys and other examination data used to administer a licensing and other examinations are exempt from disclosure.

- Real estate appraisals and engineering estimates. Where real estate appraisals or engineering or feasibility estimates and evaluations are made relative to the acquisition of property, or to prospective public supply and construction contracts, disclosure can be refused until all of the property has been acquired or the contract executed.

- Taxpayer information. Information submitted by a taxpayer in confidence, and financial data submitted in applications for financing under the Health and Safety Code, is exempt if the disclosure of information to other persons would result in unfair competitive disadvantage to the person supplying the information.

- Library circulation records. Records kept for the purpose of identifying the borrower of items available in libraries are exempt from disclosure.

- Privileged or confidential information. Records are exempt under CPRA if disclosure is exempted or prohibited pursuant to federal or state law (see California First Amendment Coalition's FAQs on this exemption).

- Employee relations. State agencies are exempted from disclosing records concerning employee relations strategy.

- Homeland security. An internal agency document assessing agency vulnerability to terrorist attack is exempt.

How to Request Records in California

Making the request

You do not need to make a written request to receive the public documents you want to inspect. If you have a routine request, start by making an informal request for the records over the telephone before invoking the law. If the agency information officer you speak with cannot grant your request over the telephone, he should be able to provide you with the necessary steps for making a formal request.

Although you are not required to do so, setting your request out in a letter may help you to get the public records you want. The letter should be addressed to the public records officer of the agency, and should include the following information, as appropriate:

- Your name, address, email address and telephone number (you have the right to make an anonymous request, but providing these details might make it easier to communicate about your request with the information officer)

- A clear description of the record(s) that you are seeking, or, if you are uncertain of how to describe the records you wish to obtain, a description of your purpose in seeking records and a request that the agency assist you to identify relevant records;

- Date limits for any search

- If you anticipate that the record may be hard to find, any search clues you can think of

- A statement that if portions of the records are exempted, the non-exempt portions of relevant records still be provided

- Limitations on pre-authorized costs or a request for a cost waiver, together with your reasons for requesting a waiver.

You can request either to view the records or to have copies made. Viewing records at the agency's office will probably be quicker, and might give you the opportunity to narrow down the list of documents you want copies of, and also reduces your copying expenses.

Fulfilling the Request

Agencies are required to provide prompt access to records. Once you make your request to inspect records, you should get immediate access to those records during the hours set by the agency for inspection of records. If you request copies, the agency must decide within ten days whether copies will be provided, except in unusual circumstances, where it may grant itself an extension of fourteen days. "Unusual circumstances" means an agency needs to:

- Search for and collect the requested records from outside the office processing the request (eg. field facilities or regional offices);

- Search for and process a voluminous amount of records in a single request;

- Consult with another agency (or another part of the same agency) having substantial interest in the determination of the request; or

- Compile data, to write programming language or a computer program, or to construct a computer report to extract data.

Payment

A government agency can only charge you the "direct cost" of duplicating records unless it is authorized by statute to charge a reasonable flat fee. In the case of documents, "direct cost" means the cost of photocopying (approximately 10 to 25 cents per page). In the case electronic data, "direct cost" can mean the cost of producing a copy of the record in electronic format (the cost of the disk, as well as the cost of constructing the record, programming and computer services if this is required).

A statutory fee may be higher than the direct cost of duplicating a record, but cannot exceed what is reasonably necessary to provide the copy. In either case, staff time spent searching for and reviewing records cannot be recovered. Although there is no fee waiver in the CPRA, agencies have the discretion to waive or reduce fees.

What Are Your Remedies in California

You have several options open to you should your request be denied. First, try to work with the information officer you are dealing with. If the agency is relying on an exemption, ask the information officer if he will waive the exemption because exemptions are permissive, not mandatory. If that fails, you can also ask the information officer to release the nonexempt portions of the record with the exempt portions removed or redacted.

If you feel frustrated by your conversations with the information officer, you ask to speak to someone more senior within the agency and explain your case.

Look to see whether the agency has any process in place to appeal the denial. Some agencies have created a formal process for administrative appeal and some municipal agencies have adopted sunshine ordinances providing for administrative review of denials. If this option is available, pursue it before starting any court action.

If administrative appeals are not available, or if your request is denied after administrative review, you are entitled to seek court review of the denial (Cal. Gov't Code §§ 5258-5260). Refer to California First Amendment Project's Q&A on using legal action to enforce disclosure. Additionally, refer to our section on Finding Legal Help for more information on how to get legal assistance to help you assess the merits of a potential lawsuit against the agency.

Jurisdiction:

Subject Area:

Access to Public Records in Florida

Note: This page covers information specific to Florida. For general information concerning access to government records see the Access to Government Records section of this guide.

You have a statutory right to inspect a vast number of Florida’s public records using the state's Public Records Act. See chapter 119, section 1 of the Florida Statutes (Fla. Stat.), which states that “all state, county, and municipal records are open for personal inspection and copying by any person.”

What Records Are Covered in Florida

What Government Bodies Are Covered

You are entitled to view the records of all state, county, or municipal units of government, as well as any other public or private entity acting on behalf of one of these agencies. See Fla. Stat. § 119.01. See Access to Government Meetings in Florida and Access to Florida Court Records for more information on how to access records from those government entities.

What Types of Records Can Be Requested

You are entitled to inspect and copy "public records," including all documents, maps, tapes, photographs, films, sound recordings, data processing software, or other material, made or received pursuant to law or in connection with the official business of any agency. Fla. Stat. § 119.011(11).

What Exemptions Might Apply

Unlike other states, where in most cases there are a limited number of exemptions, Florida has hundreds of general and agency-specific exemptions pursuant to which an agency can refuse to provide access to records. The Florida Public Records Act lists the following:

- General exemptions

- Executive branch agency exemptions

- Executive branch agency-specific exemptions

- Local government agency exemptions