Quick rule of thumb: when a judge is looking to perform an experimental legal amputation, that judge will vivisect a child molester. It’s easy to take away the rights of someone who has acted in such a bestial, inhumane manner. One of the problems with this practice is that these restrictions are later visited on less horrible people. They come first for the pedophiles, but then they may come for you.

I have written about the judicial practice of imposing Internet prohibitions on sex offenders and wondered if a court would uphold such restrictions on appeal. A recent decision by the Third Circuit, United States v. Thielemann, affirmed a decade-long ban on Internet use for a pedophile and forced me to revisit the question.

(Reminder: I am all for the punishment of child molesters. I am not questioning the State’s right to incarcerate these individuals, or monitor their behaviors if they are ever released. This discussion is arguably moot since we regularly detain pedophiles even after they have served the maximum sentence; a practice that raises a whole other set of constitutional concerns. See United States v. Comstock, SCOTUS just granted cert.)

A federal court may choose from a bevy of conditions when crafting a supervised release under 18 U.S.C. § 3583. The main restriction on impositions is found at § 3583 (d)(2), which stipulates that the restriction “involves no greater deprivation of liberty than is reasonably necessary" to deter crime, protect the public, and provide the defendant with needed correctional treatment. And when the government's main purpose is to protect children from abuse, it’s easy to argue that the end justifies practically any means.

Problem is, the deprived citizens have these pesky First and Eighth Amendments at their disposal. (Note: the Eighth Amendment protection is easily avoided, however, since these restrictions are not likely to be considered “punishment.” For example, see United States v. Salerno, 481 U.S. 739 (1987), where the court brushed aside a challenge to denial of bail by defining detention as “regulatory” rather than “punitive.”) So, it is up to the courts to determine which bans are acceptable.

The courts have done a generally good job of kicking out restrictions that seem to be arbitrarily imposed or unconstitutionally vague. In United States v. Pruden, 398 F.3d 241, 248 (3d Cir.2005), the court held that any restriction must have a strong basis to the factual record. See also United States v. Warren, 186 F.3d 358, 366 (3d Cir.1999). A sentencing court cannot arbitrarily assign alcohol treatments to sex offenders (as was the case in United States v. Loy, 191 F.3d 360 (3d Cir.1999) ("Loy I")), nor may it impose overbroad prohibitions, such as banning all forms of pornography (as in United States v. Loy, 237 F.3d 251, 267 (3d Cir.2001) ("Loy II", see a pattern here?). (Note: Under my mother’s definition of pornography, Loy would have had to avoid television, print media, and most billboards.)

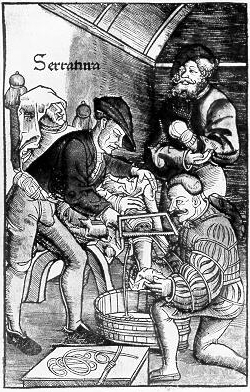

In short, a sentencing court must point to specific facts to justify a well thought out and tailored ban. Trouble arises, however, when courts can establish a nexus between the prohibited activity and previous offenses, but the prohibited activity itself has many legitimate, vital, and constitutionally protected uses. For example, even if a person has been convicted of soliciting and receiving child pornography through the post office, it would be bizarre (as well as practically impossible) to prohibit the offender from sending any mail, owning any envelops, collecting stamps, etc.

But applying a blanket prohibition is exactly what the sentencing court did do when it handed down a lifetime Internet ban in United States v. Voelker. There, the lower court prohibited Voelker, who had been convicted of downloading child pornography, “from accessing any computer equipment or any ‘on-line’ computer service at any location, including employment or education. This includes, but is not limited to, any internet service provider, bulletin board system, or any other public or private computer network.”

Voelker’s prohibition was overturned on appeal, United States v. Voelker, 489 F.3d 139 (3d Cir. 2007), in part because it would have precluded Voelker’s continued employment and disrupted his life. The court aptly pointed out that sentencing judges “should consider the ubiquitous nature of the internet as a medium of information, commerce, and communication as well as the availability of filtering software that could allow [sex offenders’] internet activity to be monitored and/or restricted.”

But, if a lifetime ban is too harsh, a decade-long digital exile seems fine. On August 3, the Third Circuit upheld a ten-year Internet ban for Paul Thielemann, who pled guilty to receipt of child pornography (18 U.S.C. § 2252A(a)(2) & (b)(1)). The sentencing judge prohibited Thielemann from “own[ing] or operat[ing] a personal computer with Internet access in a home or at any other location, including employment, without prior written approval of the Probation Office.”

The appeals court signed off on this restriction in part because, unlike the prohibition in Voelker, there was a mechanism to grant Thielemann individual permission to use some tools in some locations. (He also could own a "personal computer" [emphasis in original] so long as he did not hook it up to the Internet.) But let’s be honest, why would the probation officer EVER grant one of these requests? There is very little upside. If you say yes and the offender doesn’t reoffend, all you’ve done is made life easier for a predator. And if you say yes and the offender does reoffend? The mob will be at your doorstep, rusty pitchforks in hand. (Incidentally, it is this very same calculus that ensures mental inmates are rarely released.)

The whole prohibition seems unworkable. A blanket ban encourages non-compliance, because the Internet is indispensible. Close your eyes and think of a day without Google or Wikipedia. (Now stop crying and open your eyes.) Information on local government, parolee rights, and education (all vital elements to living on the outside) have migrated online. By banning the Internet, the government has effectively forced Thielemann to seek approval for what he can read or write. Our courts have protected the right to receive information and rejected prior restraints in the non-digital world, but for some reason some judges think the Internet is just different. But see Reno v. ACLU, 521 U.S. 844, 868-70 (1997) (indicating that First Amendment protections apply in full force to the Internet).

The courts have permitted the deprivation of other rights when it comes to convicted felons, such as the right to bear arms. But by and large, those rights do not pervade employment, commerce, and everyday life like the Internet. I rarely need to fire a gun (though I often come close as Sam edits my posts). I don’t need a gun to find a government office, or the telephone number of an aid agency, or to read about the Mongols, or to get a good deal on a stereo (actually, a gun might be very useful in that latter situation).

I’ve made this point before: without access to the Internet, a person is digitally dead. Surely there are ways to merely cripple the online predator. Ban social networks, block Twitter, prevent online video game play, monitor use. But there is no need to block the entire Internet. After all, do we really want to create a population of unemployable, under-educated, unoccupied felons?

I understand that we are talking about very, very bad men here. But these punishments are already being applied to not-so-bad guys (like the teenager who posted two nude photographs of his 16-year-old ex-girlfriend). How long before they are applied to people who violate privacy? Or commit defamation? Or download music? When it comes to offenders and the Internet, the court should operate, not amputate. We must be reluctant to sever the arteries of knowledge and self-improvement, lest we become a nation of the digital undead.

(Andrew Moshirnia is a rising second-year law student at Harvard Law School and a CMLP legal intern. He would like to take this moment to remind everyone, again, that he is not defending pedophiles, but rather is concerned that Internet bans will spread to other offenses. He asks you to please not firebomb his house. However, he will argue you should still have the right to own a stove, gasoline for your car, or other vital (but potentially fire starting) tools even if you are convicted of arson.)