Copyright 2007-25 Digital Media Law Project and respective authors. Except where otherwise noted,

content on this site is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License: Details.

Use of this site is pursuant to our Terms of Use and Privacy Notice.

content on this site is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License: Details.

Use of this site is pursuant to our Terms of Use and Privacy Notice.

[We are delighted to run this piece by our friend and Berkman Center colleague Ryan Budish - eds.]

[We are delighted to run this piece by our friend and Berkman Center colleague Ryan Budish - eds.]

In December 2011, hacktivist collective Anonymous (in)famously

In December 2011, hacktivist collective Anonymous (in)famously  Several

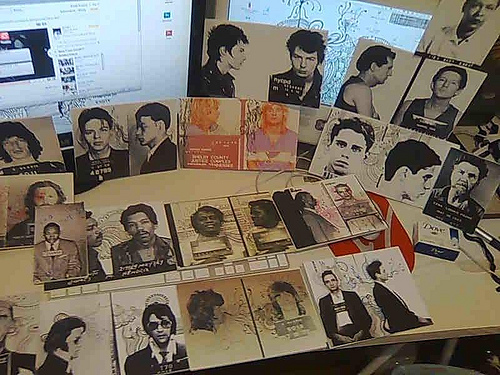

Several A new bill proposed by Florida legislator Carl Zimmermann seeks to end “mugshot websites,” a relatively new industry that exploits the marriage of the internet and open records laws in order to make a profit.

A new bill proposed by Florida legislator Carl Zimmermann seeks to end “mugshot websites,” a relatively new industry that exploits the marriage of the internet and open records laws in order to make a profit. Cell phones allow us not only to communicate with one another, but also to take and store pictures, “check in” from a location, balance our checking account, and even update our blogs. When the content of a cell phone may help the police to solve a crime, the legality of the search of both the phone and its content is of crucial importance. However, the law of warrantless searches of cell phones is not yet settled.

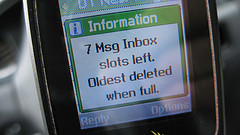

Cell phones allow us not only to communicate with one another, but also to take and store pictures, “check in” from a location, balance our checking account, and even update our blogs. When the content of a cell phone may help the police to solve a crime, the legality of the search of both the phone and its content is of crucial importance. However, the law of warrantless searches of cell phones is not yet settled.

When hearing the expression “lèse majesté,” images of the Queen of Hearts ordering heads to be chopped off ASAP may come to mind. Marie-Antoinette, the queen who was once a “majesté” in France, herself lost her head during the French Revolution. Surely, the crime of lèse majesté is now a thing of the past?

When hearing the expression “lèse majesté,” images of the Queen of Hearts ordering heads to be chopped off ASAP may come to mind. Marie-Antoinette, the queen who was once a “majesté” in France, herself lost her head during the French Revolution. Surely, the crime of lèse majesté is now a thing of the past?

The DMLP recently appeared as an amicus curiae in Commonwealth v. Busa, a case brought in Boston Municipal Court under Massachusetts's anti-counterfeiting law,

The DMLP recently appeared as an amicus curiae in Commonwealth v. Busa, a case brought in Boston Municipal Court under Massachusetts's anti-counterfeiting law,  Earlier this week the CMLP (under its new name, the Digital Media Law Project) sought leave to file

Earlier this week the CMLP (under its new name, the Digital Media Law Project) sought leave to file  Thanks to its ongoing war against the drug cartels, Mexico is one of the most dangerous places in the world for a journalist to work.

Thanks to its ongoing war against the drug cartels, Mexico is one of the most dangerous places in the world for a journalist to work.

At a recent presentation during which I reviewed a number of cases and

court rule changes regarding juror use of social media and the Internet

during trial, an audience member asked me why American courts appeared

to be so lax in the face of such juror misbehavior, such as the Texas

case in which a juror who sent a "friend" request to the defendant in a

personal injury case

At a recent presentation during which I reviewed a number of cases and

court rule changes regarding juror use of social media and the Internet

during trial, an audience member asked me why American courts appeared

to be so lax in the face of such juror misbehavior, such as the Texas

case in which a juror who sent a "friend" request to the defendant in a

personal injury case  David Perelman served in Vietnam for all of three months back in 1971, and returned to the U.S. without a scratch.

David Perelman served in Vietnam for all of three months back in 1971, and returned to the U.S. without a scratch.

The U.S. Department of State maintains a

The U.S. Department of State maintains a

Description:

James Rosen is a national news journalist for the Fox News Channel. On June 11, 2009, Rosen published an article on www.foxnews.com entitled "North Korea Intends to Match U.N. Resolution with New Nuclear Test." His Gmail email account is referenced in the case's court documents as "Redacted@gmail.com."

On May 28, 2010, Reginald B. Reyes, a Special Agent for the FBI filed an application for a search warrant for James Rosen's Gmail account, which was maintained by servers located at Google's headquarters in California. The search warrant application stated that the emails concealed information which, under Fed. R. Crim. P. 41(c), contained: (1) evidence of a crime; (2) contraband, fruits of crime, or other items illegally possessed; and (3) property designed for use, intended for use, or used in committing a crime. The warrant application stated that the search was related to a violation of 18 U.S.C. § 793, which governs the "gathering, transmitting or losing defense information."

The search warrant application included an affidavit by Agent Reyes in support of the search warrant. Reyes' affidavit said the warrant was pursuant to 18 U.S.C. § 2703 and 42 U.S.C. § 2000aa and permissible as the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia has jurisdiction over the offense under investigation. Reyes states that he believes there is probable cause that Rosen violated Section 793(d) as an aider and abettor and/or co-conspirator to Stephen Kim.

That same day, a search and seizure warrant was issued by a U.S. Magistrate Judge to be executed on or before June 11, 2010. The warrant granted the search of electronic e-mails and other electronic data of Rosen's account, and permitted the officer executing the warrant to delay notice to Rosen for 30 days under 18 U.S.C. § 2705. An attachment to the issued warrant stated that Google, Inc. was not permitted to notify "any other person, including the subscriber(s) of Redacted@gmail.com" of the warrant's existence. Google, Inc. was required to make exact duplicates of all information from the email account and send this information to Agent Reyes in overnight mail or facsimile. The attachment asked for any commuications between Rosen's account and 3 other accounts, including anothe Gmail account and two Yahoo! mail accounts; the usernames of all three accounts are also redacted in the public record. The warrant attachment referenced Rosen's connection to Stephen Kim, who was under investigation by the FBI for allegedly telling a reporter that North Korea may test a nuclear bomb.

On May 21, 2013, the government filed a motion to unseal entire docket of Rosen's case, including the application for the search warrant, the attachment to the warrant, Reyes' affidavit, and the granted warrant, with only names and dates of birth redacted for privacy reasons.

On May 22, 2013, the court granted the government's motion in a memo and order that directed the case to be a matter of public record. The memo detailed clerical errors which stalled the placement of the redacted warrant and related materials into public record. The memo apologized for the administrative errors and instituted the inclusion of a new tab on the Court's website solely for the publication of search warrants. Executed warrants will be part of the public record unless a "separate sealing order is entered to redact all or portions" upon a showing by the government as required by United States v. Hubbard, 650 F.2d 293 (D.C. Cir. 1980) and Washington Post v. Robinson, 935 F.2d 282 (D.C. Cir. 1991).

In a separate order that same day, the court ordered that the Clerk place on the public docket a redacted version of the government's motion to unseal entire docket and that the government produce unredacted versions of all unsealed material to the defense in United States v. Stephen Jin-Woo Kim.

-->