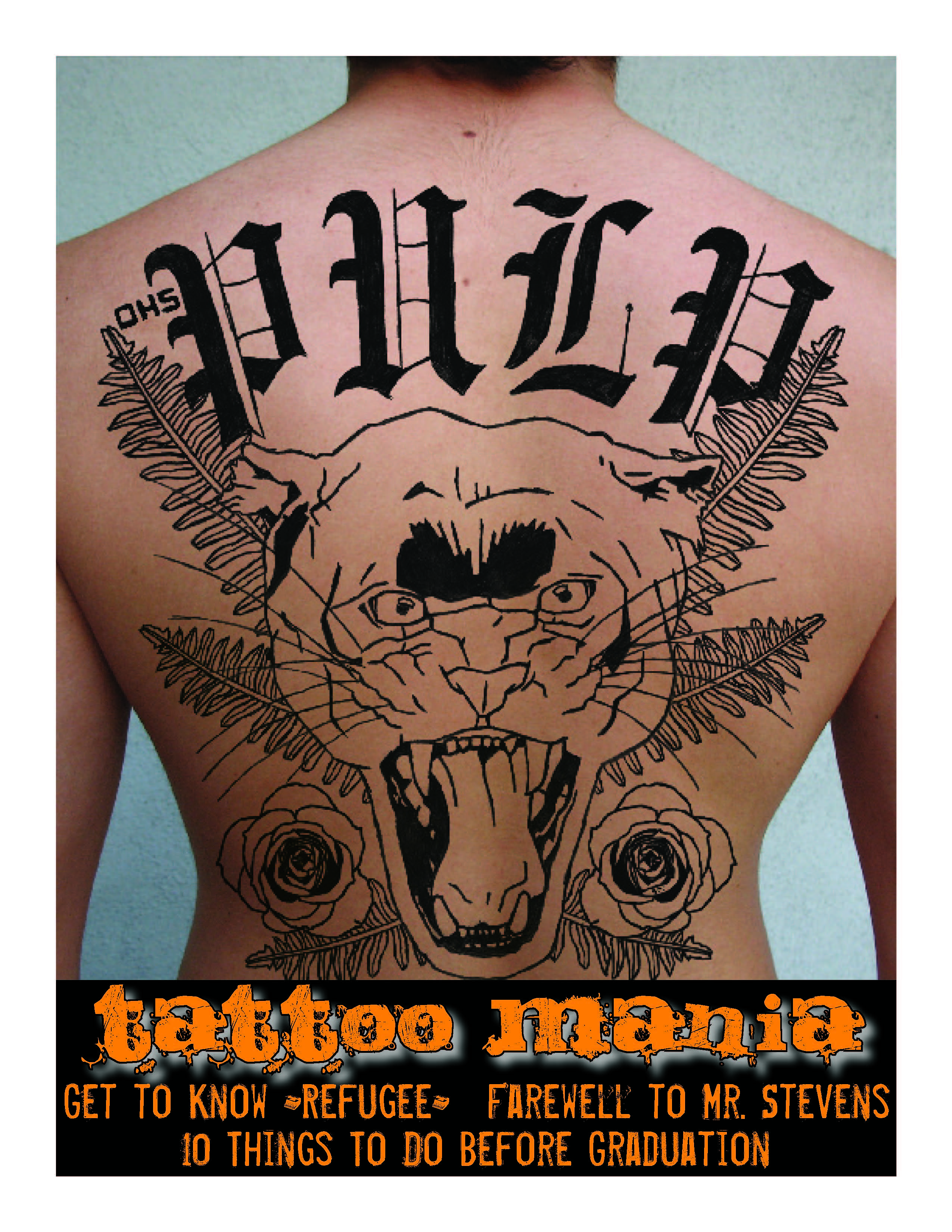

Another week, another restriction of student speech. S.K. Johnson, the principal of Orange High School in (where else?) Orange, California, has confiscated copies of a student magazine prior to publication. His main complaint about the latest issue of PULP concerns the cover, which features a faux full-back tattoo with the publication’s name and a picture of a panther, the school mascot. The principal alleges that the image promotes gang life and might encourage students to get tattoos, singling out the use of Old English font to create “gangster-style writing.”

Another week, another restriction of student speech. S.K. Johnson, the principal of Orange High School in (where else?) Orange, California, has confiscated copies of a student magazine prior to publication. His main complaint about the latest issue of PULP concerns the cover, which features a faux full-back tattoo with the publication’s name and a picture of a panther, the school mascot. The principal alleges that the image promotes gang life and might encourage students to get tattoos, singling out the use of Old English font to create “gangster-style writing.”

While the school has a legitimate interest in preventing the glorification of gang culture, one of Mr. Johnson’s proposed solutions – to affix an addendum or edit the accompanying article on student tattoos to indicate that tattoos are permanent – demonstrates that this is not actually his primary concern. Although it may be helpful for students to be reminded of the difficulty of tattoo removal, such a concern should not give a school principal the legal right to suppress student speech. Despite the essentially unlimited reach of Hazelwood with regard to school-sponsored speech (discussed in last week’s post), sanctioning censorship in order to protect students from making bad decisions on skin art almost certainly pushes it too far. Furthermore, according to Student Press Law Center attorney advocate Adam Goldstein, California state law has more stringent restrictions on censoring student speech, a position supported by a recent paper in the UC Davis Journal of Juvenile Law & Policy.

If there were legitimate concerns over gang promotion, the school would be within its rights to prevent the publication of PULP. But it is hard to argue that the magazine cover in question actually does promote gang activity. Although many gangs do use tattoos for identification, it is the design, and not the mere fact of having a tattoo, that serves as a gang marker. Furthermore, neither Old English font nor tattoos are presumptively indicative of gangs. Old English is used as the flag font for a number of highly reputable newspapers without known gang affiliations. And tattoos are becoming more widely accepted in the general population, with more than a third of Americans aged 18 to 29 sporting at least one. Tattoos have also long been prevalent in the armed forces. Even professionals are getting in on the tattoo bandwagon, with Inked Inc. hosting community pages for tattooed academics, scientists, medical professionals, and even stodgy lawyers.

Hopefully the students and school administration can come up with a mutually agreeable solution to this impasse. While the promotion of gang activities has no place in a school setting, this should not be used as an excuse to censure innocuous student expression.

(Lee Baker is a rising second-year law student at Harvard Law School and a CMLP legal intern.)