It used to be that mugshots were kept well out of the view. Despite being public records in many states, walls of bureaucracy and simple physical inaccessibility (due to the photos being locked in a police station somewhere) kept them largely out of the public eye.

It used to be that mugshots were kept well out of the view. Despite being public records in many states, walls of bureaucracy and simple physical inaccessibility (due to the photos being locked in a police station somewhere) kept them largely out of the public eye.

But the Internet has changed that. Now, those same photos are uploaded to the web on tens, maybe even hundreds, of police and sherriff websites, giving rise to two new online businesses: the mugshot aggregation website and its opposite number, the mugshot removal website. But as David Kravets wrote in Wired, the interaction of these two types of website is more complicated than it seems. And their dealings call into question the reluctancy of states to centralize public records online in the first place.

Kravets explains that reputation companies, like RemoveSlander.com, are players in an emerging “mugshot racket” that feature websites with millions of photos and a convenient way to remove them: money. For $399, RemoveSlander will remove a mugshot featured on the popular — but apparently unaffiliated — site, Florida Mugshots, for example. According to the article, the company does this by paying part of that fee to the mugshot site’s owner. “On the surface, the mug-shot sites and the reputation firms are mortal enemies,” Kravets wrote. “But behind the scenes, they have a symbiotic relationship that wrings cash out of the people exposed.”

These companies are now emerging in Florida due to the state’s broad public record laws that allow individual mugshots to be easily obtained. When it comes to these photos, most states consider your face — be it beat-up, distraught, or half-shaven — to be a public record. (Click here to run a 50-state comparison.)

All this openness isn’t necessarily a bad thing. I could quote Justice Brandeis about how well sunlight disinfects, but ultimately it’s a matter of providing information to the public about police activity and those who are arrested for crimes. The lack of privacy is a worthwhile price to be paid for such accountability. But what about the price to be paid for keeping public records, well, less public?

According to Wired, Rob Wiggen, who runs the Florida Mugshots site, is an ex-con now making money legitimately via mugshot-takedown fees. Power to him. But as Wiggen readily admits, his own mugshot will not be found on his site — and neither will those of others who pay up. What bothers me about this isn’t so much the exploiting of state public record laws, but the lack of a central repository for public records that allows such exploitation to occur. Wiggen uses scraping software to collect the mugshots from about 60 different searchable websites run by local law enforcement. When aggregated, those photos can become a valuable database.

But this one is obviously incomplete. The site is missing the faces of all those who have the financial means and desire to pay for their mugshot’s removal. With Wiggen’s site ranked far higher in “Florida mugshot” searches than any police department, only the wealthy and informed get to limit their indiscretions to the relative obscurity of a single county website.

When it comes to open records, these varying degrees of publicness are bothersome. While all Florida mugshots are public under the law, some are more visible than others. In the words of Kravets, companies can choose which mugshots stay hidden behind police CGI search scripts, and which will display prominently in Google searches. We can debate the merits of certain open record laws, consider the balance between transparent government and individual privacy, but if the law makes a record public, it should be visible as well. What good are records that no one sees? Given the way most people get their information, Google has become the gatekeeper here, not some county sheriff.

Kravets told the story of Philip Cabibi who typed his name into Google one night and found his mugshot listed on the first page of results. The 31-year-old had been arrested a few years earlier for driving while drunk in Florida. His face now featured prominently in Google search results because of Florida Mugshots. Cabibi hired RemoveSlander, paid $399 and voilà, no more mugshot. Cabibi’s photo is still a public record. There is nothing preventing another publisher from posting it on his or her website, but to Cabibi at the time, the fee was money well spent. Most people get their information via a Google search, not from requesting the records of an individual police department. While public, Cabibi’s photo was essentially no longer visible. It’s as if the only newspaper in town left a name out of its weekly police blotter because it was paid by that person to do so. It’s the publisher’s prerogative to play favoritism, but the public deserves a better way to obtain information.

The best access to records — be them town board meeting minutes or mugshots — shouldn’t be through a site that is paid for protecting the privacy of one individual over another. It should come from a government body that prohibits that patronage in favor of accuracy and context. There should be a central hub for all public records and not their current scattered online state. Without such a repository, the public is left with private enterprises like Florida Mugshots. It’s a reality that is likely to remain, as state offices are quite fond of collecting FOIA fees. (Consider this bill being proposed in Illinois. If passed, the legislation would actually discourage local governments from posting information online.)

Until the states get involved in aggregating public records, we're left with private entities like these mugshot websites to fill the gap. And while these sites make a great deal of public information readily accessible — Florida Mugshots alone has more than 4 million mugshots in its possession — I can’t help but think of the smaller number that are missing. States need to get better at turning their public records into visible ones.

Justin graduated from Suffolk University Law School in 2011, and is currently a law clerk at the Boston firm Prince Lobel & Tye. You can contact him through his website, JustinSilverman.com, and follow him on Twitter at @MediaLawMatters.

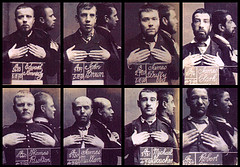

(Image of mugshots from Glasgow's Barlinnie jail circa 1890 courtesy of Flickr user angus mcdiarmid licensed under a Creative Commons BY NC license.)