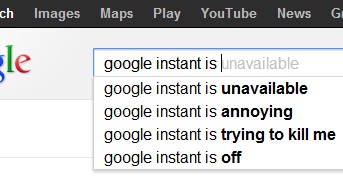

Google searches employ two features: autocomplete and Google instant. These work together to complete your search terms and to automatically load search results while you're typing. While you're probably thankful for the few seconds this saves, or the way it triggers a connection you couldn't recall, Bettina Wulff (wife of former German President Christian Wulff) would be unlikely to agree with you these days. Type Wulff's name into Google, and the first autocomplete suggestions you'll see are "Bettina Wulff escort," and "Bettina Wulff prostituierte." Wulff is now suing Google for defamation, along with German TV host Günther Jauch and over 30 bloggers and media outlets. Wulff's suit against Google focuses on the results of this autocomplete feature.

Google searches employ two features: autocomplete and Google instant. These work together to complete your search terms and to automatically load search results while you're typing. While you're probably thankful for the few seconds this saves, or the way it triggers a connection you couldn't recall, Bettina Wulff (wife of former German President Christian Wulff) would be unlikely to agree with you these days. Type Wulff's name into Google, and the first autocomplete suggestions you'll see are "Bettina Wulff escort," and "Bettina Wulff prostituierte." Wulff is now suing Google for defamation, along with German TV host Günther Jauch and over 30 bloggers and media outlets. Wulff's suit against Google focuses on the results of this autocomplete feature.

Years ago, rumors began that Bettina Wulff had a former career as a prostitute named "Lady Victoria," possibly intended to damage Christian Wulff's political career. Wulff denies these rumors in her new biography, and asserts that they have harmed her reputation and family life. Wulff has filed a defamation suit in the Hamburg District Court to force Google to remove these false, damaging terms from the results of its autocomplete function. So far, Google has not removed the result terms; according to Spiegel Online, the company denies responsibility and claims that the products of the autocomplete function are driven by an algorithm relying on, among other things, popular search terms selected by users.

Without going into too much detail about the search algorithms, suggested autocomplete searches are all real searches done by Google users. The algorithm considers popularity foremost, but also considers geography, relevance, and your prior search history, among other objective factors, when providing these results. In this manner, then, Google's autocomplete feature and Google instant consider more than popularity, and there are times in which Google's algorithms limit search results or alter their ranking to reflect policy considerations.

Thus, if Google chose to alter the results of a search for Bettina Wulff, it would not be the first time Google has censored or altered Autocomplete results for policy reasons. For example, pressure from the entertainment industry and government officials has impacted Google's searches. In an attempt to fight piracy, Google's search function will not complete words such as "bittorrent", "torrent" and "rapidshare." Similarly, up until recently, Google had blocked the term "bisexual" from autocomplete search results, only removing "bisexual" from its banned words after a campaign by BiNet and other advocacy groups. Should false speech, particularly that injurious to its subject, be its next consideration?

Bettina Wulff is not the first individual to sue Google over false autocomplete results, and there is some precedent for finding defamation arising out of search results. Earlier this year in Japan, a man sued Google after its autocomplete results linked him to a crime he had never committed, allegedly resulting in irretrievable damage. The Japanese court ordered Google to delete the identified "false" autocomplete terms. Google was also fined last year when autocomplete suggested "crook" after the name of a French insurance company, and an Italian court ordered Google to filter out libelous search results that falsely suggested fraud. It would not be surprising, then, if a case tried in Germany, where defamation is codified in the criminal code, follows the lead of these other nations.

As in many other situations involving liability for content, this case highlights American exceptionalism in the realm of free speech. The United States takes a very speech-protective approach to libel, particularly with respect to public figures like Wulff. While the specific elements of defamation vary slightly from state to state, to establish liability for defamation in the case of public figures, the injured party must prove that the speaker acted with actual malice -- i.e., knowledge of falsity or a high degree of awareness of probable falsity.

Under this rigorous standard, it seems unlikely that this case or a similar defamation case would succeed in a U.S. court. Google, in devising its algorithm, did not knowingly intend to publish false statements of fact. At most, a court might determine that Google failed to take adequate precautions against defamatory combinations of words popping up, but "actual malice" depends on knowledge of falsehood and not objective perceptions of negligence. Moreover, even under a negligence standard it might be unreasonable to expect Google to police for truthfulness every potential autocomplete suggestion resulting from an inquiry on its search engine.

In addition, popularity is the primary factor considered in producing search results, and with regards to this element, Google is not itself speaking in a traditional manner but rather collecting and presenting the speech of others. As such, Google would likely be immune in the U.S. under Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, which prohibits online services from being treated as the publisher of user-generated defamatory content. Although Google's autocomplete function calls particular prior searches by other users to one's attention, it apparently does not modify those searches in a way that would transform Google into a content creator.

Just to see if the issue was specific to Google, I also ran a search for Bettina Wulff on Bing, which returned the same results (though in slightly altered order) as one on Google. As Bing uses a different search algorithm, this supports Google's assertion that the results are the product of popular searches and suggests that the factors other than popularity have a minimal, if not negligent, role in determining these results. If Google, then, relies on the popularity of searches to determine its results, and these searches reflect the speech of countless individuals as measured objectively, can Google possibly be found to have acted with subjective awareness of probable falsity? While Bettina Wulff's case as tried in Germany won't provide us with that answer, it's only a matter of time before a U.S. defamation case arising out of autocomplete results raises these questions directly.

Kristin Bergman is a 2L at William & Mary Law School. After using autocomplete and Google instant, she discovered a Kristin Bergman committed to yoga and massage. This isn't her.

(Image captured from Google search run using Google Chrome on September 26, 2012.)