On Monday the First Circuit released an important opinion addressing copyright and news photography, in Harney v. Sony Pictures Television, Inc., No. 11-1760 (1st Cir. Jan. 7, 2003). The case is related to the famous "Clark Rockefeller" incident. For those unfamiliar, "Clark," a wealthy Boston socialite who was purportedly a member of the Rockefeller family, kidnapped his daughter and fled Boston in July 2008. This lead to a nationwide manhunt that ended a little over a week later in Baltimore. After he was apprehended it was revealed that "Clark" was actually Christian Gerhartsreiter, a German immigrant that had come to the United States as a teenager and since then assumed many different fake identities, including that of Boston socialite "Clark Rockefeller." After a conviction for parental kidnapping, Gerhartsreiter is now in California, standing trial for a 1985 murder.

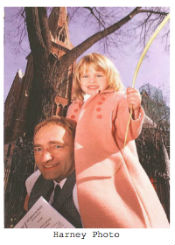

If you have one image in your mind from this famous news story, it's probably this photo:

This photo was taken by freelance photographer Donald Harney for a piece in the Beacon Hill Times. The photo was used by state and federal police agencies during the manhunt for Gerhartsreiter, where it saw widespread dissemination.

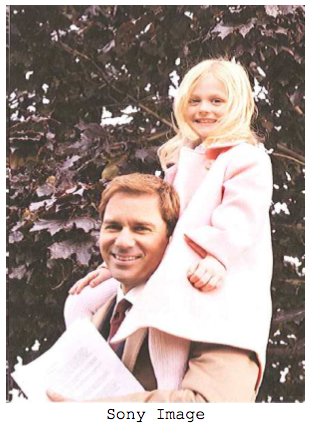

Sony Pictures thought the story of "Clark Rockefeller" so riveting that they decided to create a made-for-TV movie called Who is Clark Rockefeller? that subsequently aired on Lifetime. True to the police-procedural genre, the movie goes into detail about the manhunt and includes a "last known photo" that is based on the Harney photograph:

Harney subsequently sued Sony Pictures and A&E Television for copyright infringement. After the district court found for Sony on summary judgment, the First Circuit affirmed in a long and thoughtful opinion, holding that the two images are not "substantially similar" for copyright purposes. The court, under the pen of Judge Lipez, comes to this conclusion after a casebook-worthy analysis of both copyright infringement doctrine generally and copyright in photographs specifically.

As devout readers of our legal guide already know, a standard copyright infringement claim requires a plaintiff to show three things: that the plaintiff has a valid copyright in a work, that the defendant had access to the work (or, stated conversely, that the work was not an independent creation), and that the two works are "substantially similar."

"Substantial similarity" has its doctrinal difficulties, but its application essentially boils down to what you already did two paragraphs ago after I displayed those photographs: look at the two works and see whether the expressive nature of each is essentially the same. Built within that question is a value judgment as to what is "protectable" and what is not within any given genre of expression. (For example, comparison of two blues songs will likely disregard the similarity in chordal structure, as virtually all blues songs have the same chordal structure. This is called "scènes à faire" in copyright doctrine.)

But another wrinkle is added when dealing with depictions of things that exist in the real world (a universal issue in news photography). As part of its centuries-old balance between protecting works while not stifling creativity and open expression, copyright protection does not extend to ideas, facts, or elements not original to the author. In other words, the subjects themselves, the items that were not placed there by the photographer, and things occurring in nature around them are not protectable under copyright. This is not a gap or a loophole in protection; this is something we include to make sure that others are free to create and disseminate works of their own.

To ensure that these unprotectable elements don't accidentally become de facto protected through a substantial similarity analysis, courts approach the infringement question by first dissecting the elements in the photograph to determine what is protected, and then comparing the works for similarity. The Harney court's explanation of this task is one of the better ones I've seen:

The court initially "dissect[s]" the earlier work to "separat[e] its original expressive elements from its unprotected content." … The two works must then be compared holistically to determine if they are "substantially similar," but giving weight only to the protected aspects of the plaintiff's work as determined through the dissection. We have explained that two works are substantially similar if "'the ordinary observer, unless he set out to detect the disparities, would be disposed to overlook them, and regard their aesthetic appeal as the same.'" … This assessment, of course, must be informed by the dissection analysis.

(Citations omitted, emphasis in original.) Of course, courts must also be mindful not to atomize and over-dissect images into non-protectable elements, and thus prevent any finding of copyright protection at all. For other good examples of this balance playing out, see the Eleventh Circuit in Leigh v. Warner Brothers and the First Circuit's earlier cases about scented candle labels and toys depicting tree frogs.

Applied here, the First Circuit found that many of the elements of the photo were unprotectable: the daughter riding piggyback on her father's shoulders, the Palm Sunday symbols they carried, the clothes they were wearing, and the Church of Advent's exterior architecture. None of these were chosen, posed, or expressed by Harney. On the other hand, the composition of the photograph, the framing of the church in the background, and the use of light and shadow all were found to be protectable. Unfortunately for Harney, these elements are also the ones most notably absent from Sony's recreation (save the waist-up composition of the subject) and thus the court found no substantial similarity.

Harney argued both in briefing and at oral argument that application of the dissection analysis unfairly limits the copyright protection of news photography, and thus undercuts Congress's intended incentive regime. The court addressed that question as follows:

Applying these principles to news photography, which seeks to accurately document people and events, can be especially challenging. "[A]rtists [ordinarily] have no copyright in the 'reality of [their] subject matter," … and the news photographer's stock-in-trade is depicting "reality." Yet "the photographer's original conception of his subject" is copyrightable. … Courts have recognized originality in the photographer's selection of, inter alia, lighting, timing, positioning, angle, and focus. … Photographers make choices about one or more of those elements even when they take pictures of fleeting, on-the-spot events. Additional factors are relevant when the photographer does not simply take her subject "as is," but arranges or otherwise creates the content by, for example, posing her subjects or suggesting facial expressions.

(Citations omitted.) Later in the opinion the court went on to add:

We have sympathy for Harney's concern about the protection afforded to spontaneous photography, which by its nature consists primarily of "[i]ndependently existing facts." Indeed, assuring copyright protection for fleeting images of newsworthy persons or events encourages freelance photographers to continue creating new images, advancing the goal of the Constitution's copyright clause "to promote the Progress of . . . useful Arts[.]" … We disagree, however, that application of the ordinary dissection analysis will deny copyright protection for such works. As described above, Harney created an original protectible image. His photograph may not be reproduced in its entirety without his permission unless the copier is able to prove fair use. Nor may the original components noted above, including the particular juxtaposition of the father-daughter and the church, be freely copied if an ordinary observer would view the resulting image as "substantially similar" to his original.

Certainly, the value of an image can change over time along with observers' attitudes toward its subject matter. Photographs of celebrities as children or unusual images of notable buildings later demolished may become of wide interest decades after they were taken. Likewise, the actual identity of the father and child in Harney's photograph became important only after [the child's] abduction. While Harney should benefit from the added interest in his photograph, as he did through the payments from Vanity Fair and other publications, such newfound interest does not change the originality vel non of the individual components of the work. It does not, in other words, change Harney's creative contributions to the Photo.

(Citations omitted, emphasis in original.)

The idea that the First Circuit is getting at with this quote is an important one. Indisputably, Sony copied Harney's photo here, and in doing so appropriated some of the public goodwill attributable to Harney's photo. But that does not alter the scope of copyright protection. We do not allow creators to assert greater monopolies over their expressions simply because they are popular, whether it comes through being a quality work, a serendipitous documentation, or (in the case of Harney) a little of both. The law is crafted to allow extrinsic compensation for higher popularity, while still allowing the rest of us to freely discuss, describe, and depict the true things about the world, even when doing so means referencing creative works without authorization.

Andy Sellars is a staff attorney at the Digital Media Law Project and the Dunham First Amendment Fellow at the Berkman Center for Internet & Society. His photography is featured neither in Lifetime docudramas nor on police wanted posters.(Images from the appendix to the court's opinion by Donald Harney and Sony Pictures Television, Inc., respectively.)