For me, thinking about one of the Obama administration's latest initiatives to keep us all safe online is like one of those pattern recognition puzzles (you know, like "What is the next term in this sequence: O, T, T, F, F, S, S, E, N, __?"). Here, the sequence is:

For me, thinking about one of the Obama administration's latest initiatives to keep us all safe online is like one of those pattern recognition puzzles (you know, like "What is the next term in this sequence: O, T, T, F, F, S, S, E, N, __?"). Here, the sequence is:

cyber bullies, scammers, gangs, sexual predators, ________?

The pattern, you see, is perceived online threats against which the White House has taken action. In a February 5 post on the White House Blog, we get the administration's answer to what goes in the next blank: "online radicalization to violence."

Huh.

The White House explains its concerns this way:

Violent extremist groups ─ like al-Qa’ida and its affiliates and adherents, violent supremacist groups, and violent “sovereign citizens” ─ are leveraging online tools and resources to propagate messages of violence and division. These groups use the Internet to disseminate propaganda, identify and groom potential recruits, and supplement their real-world recruitment efforts. Some members and supporters of these groups visit mainstream fora to see whether individuals might be recruited or encouraged to commit acts of violence, look for opportunities to draw targets into private exchanges, and exploit popular media like music videos and online video games.

Al-Qa'ida, violence, music videos AND video games? I'll get my pitchfork.

Except, see, I'm pretty sure I remember reading something along the following lines:

[T]he constitutional guarantees of free speech and free press do not permit a State to forbid or proscribe advocacy of the use of force or of law violation except where such advocacy is directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to incite or produce such action. "[T]he mere abstract teaching . . . of the moral propriety or even moral necessity for a resort to force and violence, is not the same as preparing a group for violent action and steeling it to such action."

Ah, yes. That's right -- it was Brandenburg v. Ohio, the 1969 U.S. Supreme Court case that held that the First Amendment required the reversal of the conviction of a Ku Klux Klan leader under an Ohio statute that prohibited "advocat[ing] . . . the duty, necessity, or propriety of crime, sabotage, violence, or unlawful methods of terrorism as a means of accomplishing industrial or political reform" and "voluntarily assembl[ing] with any society, group, or assemblage of persons formed to teach or advocate the doctrines of criminal syndicalism."

Basically, you're allowed to talk about violence in the United States. You're allowed to be "divisive." You're even allowed to argue that violence is an appropriate response to the ills you perceive in the government or the world at large. You are certainly allowed to publish and to play violent video games, even realistic ones where you can choose a side opposing the United States. Only when your speech gets to the point of "inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to incite or produce such action" do you leave the protection of the First Amendment.

The White House isn't (yet) attempting to pass laws to ban this content, which would pretty clearly be unconstitutional, but it's certainly considering normative and technological measures:

As a starting point to prevent online radicalization to violence in the homeland, the Federal Government initially will focus on raising awareness about the threat and providing communities with practical information and tools for staying safe online. In this process, we will work closely with the technology industry to consider policies, technologies, and tools that can help counter violent extremism online. Companies already have developed voluntary measures to promote Internet safety ─ such as fraud warnings, identity protection, and Internet safety tips ─ and we will collaborate with industry to explore how we might counter online violent extremism without interfering with lawful Internet use or the privacy and civil liberties of individual users.

Two problems: First, norms and technological tools are blunt instruments when it comes to chilling speech. Even if the White House were focused on preventing Brandenburg-style incitement (which I don't get from this blog post, but which would seem to be essential to avoid "interfering with lawful Internet use or the ... civil liberties of individual users"), it would be virtually impossible to fine-tune the "practical information and tools" that it intends to deploy at a community level so that they would not be applied more broadly.

Second, and perhaps more important, is the fact that the White House is attempting to accomplish its goals without overt or direct state action. The government will of course attempt to wash its hands of any industry overkill, because these would be "voluntary" measures undertaken by private parties. The First Amendment danger of indirect state action is, if anything, more pernicious than direct legislation subject to scrutiny by Congress and the courts.

To get back to the pattern puzzle with which I opened this post, the White House states that the above approach "is consistent with Internet safety principles that have helped keep communities safe from a range of online threats, such as cyber bullies, scammers, gangs, and sexual predators." But threats of physical violence, fraud, organized criminal activity, and sexual crimes all pretty clearly fall outside the First Amendment; radical speech doesn't really fit in this list.

Also note that the government platform tapped to lead this charge is OnGuard Online, managed by the Federal Trade Commission. True, the Department of Homeland Security and several other agencies are involved with the site, but the FTC? A quick look at OnGuard Online reveals information about phishing and online scams, evaluating consumer products online, protecting online privacy, protecting children online, and securing computers and networks -- all of which could be interpreted as falling within the FTC's remit. Protecting "the homeland" against "violent radicalization"? Not so much.

I'll end with another pattern puzzle:

Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire, Brandenburg v. Ohio, Texas v. Johnson, Brown v. Entertainment Merchants Association, ________________?

---

Jeff Hermes is the Director of the Digital Media Law Project.

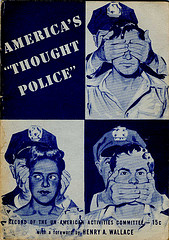

(Photo courtesy of Brandeis University's Radical Pamphlet Collection pursuant to a Creative Commons CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 license.)