This July, Verizon Communications and MetroPCS Communications filed a brief in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit, arguing that the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) lacks the authority to enact net neutrality rules and that these neutrality rules are unconstitutional under the First and Fifth Amendments. Now, debate over the FCC's approach to net neutrality is not a recent development. In fact, even the predecessor to the net neutrality rules, the policy statement for net neutrality principles, was challenged and ultimately defeated in a case brought by Comcast. Still, Verizon's latest case and public debate may shed light on the liberties at stake with the net neutrality rules and how to best balance everyone's interests.

This July, Verizon Communications and MetroPCS Communications filed a brief in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit, arguing that the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) lacks the authority to enact net neutrality rules and that these neutrality rules are unconstitutional under the First and Fifth Amendments. Now, debate over the FCC's approach to net neutrality is not a recent development. In fact, even the predecessor to the net neutrality rules, the policy statement for net neutrality principles, was challenged and ultimately defeated in a case brought by Comcast. Still, Verizon's latest case and public debate may shed light on the liberties at stake with the net neutrality rules and how to best balance everyone's interests.

The Net Neutrality Principles and Comcast v. FCC

Before formalizing its official net neutrality rules, the FCC adopted net neutrality principles in a policy statement in 2005. In this policy statement, the FCC outlined four principles to "to ensure that broadband networks are widely deployed, open, affordable, and accessible to all consumers":

- To encourage broadband deployment and preserve and promote the open and interconnected nature of the public Internet, consumers are entitled to access the lawful Internet content of their choice.

- To encourage broadband deployment and preserve and promote the open and interconnected nature of the public Internet, consumers are entitled to run applications and use services of their choice, subject to the needs of law enforcement.

- To encourage broadband deployment and preserve and promote the open and interconnected nature of the public Internet, consumers are entitled to connect their choice of legal devices that do not harm the network.

- To encourage broadband deployment and preserve and promote the open and interconnected nature of the public Internet, consumers are entitled to competition among network providers, application and service providers, and content providers.

In 2007, Free Press and Public Knowledge filed a complaint with the FCC, having noticed that Comcast was interfering with subscribers' use of peer-to-peer networking applications. In response, using its authority under the Communications Act of 1934 § 4(i) (which authorizes the Commission to "perform any and all acts, make such rules and regulations, and issue such orders, not inconsistent with this chapter, as may be necessary in the execution of its functions"), the FCC sanctioned Comcast for violating its net neutrality policy statement, improperly slowing traffic to BitTorrent. Comcast complied, then appealed this order in Comcast Corporation v. FCC, 600 F.3d 642 (D.C. Cir. 2010). In April 2010, the Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit held that the FCC did not have constitutional authority nor sufficient statutory authority to enforce its policy statement against Comcast by prohibiting its interfering with costumers' Internet use. The Court held that under American Library Association v. FCC, 406 F.3d 689 (D.C. Cir. 2005), the FCC would only have this authority if it were "reasonably ancillary to the . . . effective performance of its statutorily mandated responsibilities," and the FCC failed to prove this.

The Net Neutrality Rules

After much development and compromise, the net neutrality rules, intended to replace the principles, were finalized in the FCC's order for "Preserving the Open Internet Broadband Industry Practices" (25 F.C.C.R. 17905 (rel. Dec. 23, 2010), 76 Fed. Reg. 59192). The order was released in late 2010 (after passing by a 3-2 vote) and published officially in late 2011. Simplified, the order creates three rules in regards to net neutrality, sometimes distinguishing between broadband and wireless networks:

- Internet service providers (ISPs), whether wired or wireless, must be transparent by releasing their network management procedures and performance characteristics.

- ISPs are prohibited from blocking lawful content on the Internet. Fixed broadband network providers may not block any lawful content, services, applications, or devices. In addition to these, wireless providers may not block Web sites (though the rule is more lenient for applications and services, only extending to access to those applications and services specifically competing with the provider).

- Fixed broadband network providers may not unreasonably discriminate against network traffic.

On policy grounds, the FCC argues that this order encourages fair competition between companies and preserves the Internet as we have always known it. In this vein, the executive branch described the net neutrality rules as "an enforceable, effective, but flexible policy for keep the Internet free and open."

In terms of legal justifications, the FCC continues to assert its power as an agency under the Communications Act of 1934. In part, the FCC points to Section 4(i), which authorizes the Commission to "perform any and all acts, make such rules and regulations, and issue such orders, not inconsistent with this chapter, as may be necessary in the execution of its functions." In addition, the FCC argues that its "broad authority" is derived from Communications Act as "viewed as a whole."

Verizon's Challenges

This is not the first time Verizon and MetroPCS have challenged the FCC's authority to put net neutrality rules into practice - the companies filed an appeal to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit in January, 2011, but the Court dismissed the case, holding that it was not ripe because the FCC's order had yet to be published in the Federal Register.

Now, within the first year of the order's effect, Verizon and MetroPCS have filed another challenge to these net neutrality rules in the Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit. In their joint brief in Verizon v. Federal Communications Commission (No. 11-1355), Verizon and MetroPCS make several arguments against the FCC and net neutrality rules, challenging the FCC's authority as well as the neutrality rules themselves. They argue:

- The rules directly conflict with the Stored Communications Act, which forbids the FCC from applying common-carrier regulation to broadband Internet access.

- As in Comcast v. FCC, The FCC lacks statutory authority for the rules and has not demonstrated that the neutrality rules are necessary to achieve any statutorily-mandated task.

- The neutrality rules violate the First Amendment's free speech protections as, "broadband networks are the modern day microphone by which their owners engage in First Amendment speech."

- The neutrality rules violate the Fifth Amendment's private property rights of broadband network owners as they amount to government compulsion to turn over their private property for use by others without compensation."

- The neutrality rules are arbitrary and capricious.

As Jon Healey notes, "In essence, the debate boils down to a question of what freedom online is most worth preserving: the freedom from regulation, or the freedom from interference by ISPs." The FCC's net neutrality rules aim to balance the rights of providers and consumers, but such a balance is difficult to achieve. Do these rules go too far or not far enough? While Verizon's suit argues the rules are excessive, net neutrality supporters like Free Press challenge the seemingly arbitrary distinctions between wired and wireless Internet and want the rules to be stronger.

This battle is not taking place in isolation. While challenges to the FCC's net neutrality rules make their way into court once again, the FCC, companies, organizations, and individuals alike are rallying for preservation of their interests in the Internet. There is a new Declaration of Internet Freedom, a movement to "save" the Internet, and the FCC has even established a new Open Internet Advisory Committee (with representatives from AT&T, Comcast, the Center for Democracy and Technology, and more, chaired by Harvard's Jonathan Zittrain) to "track and evaluate the effects of the FCC's Open Internet rules, and provide any recommendations it deems appropriate to the FCC."

In the meanwhile, the FCC has until September to reply to Verizon's complaint. While this debate continues publicly and as cases against the FCC progress, we may come closer to determining the best balance between protecting the free speech rights of ISPs and those of consumers.

Kristin Bergman is an intern at the Digital Media Law Project and a rising 2L at William & Mary Law School. Kristin supports an open Internet - she just doesn't know the best way of achieving that, yet.

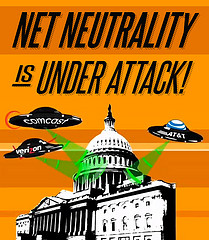

(Photo courtesy of Flickr user Free Press Pics pursuant to Creative Commons CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 license)

Comments

Update

Case update: The D.C. Circuit ruled on Verizon v. FCC earlier today, invalidating the FCC's net neutrality rules. The Court held, "[E]ven though the Commission has general authority to regulate in this arena, it may not impose requirements that contravene express statutory mandates. Given that the Commission has chosen to classify broadband providers in a manner that exempts them from treatment as common carriers, the Communications Act expressly prohibits the Commission from nonetheless regulating them as such. Because the Commission has failed to establish that the anti-discrimination and anti-blocking rules do not impose per se common carrier obligations, we vacate those portions of the Open Internet Order." The full opinion can be found here.